|

|

|

Volume VII |

June 2002 |

Number VI |

|

|

Send in the Goats: They'll Eat Anything By Kay MatthewsPeñasco Schools Participate in C.H.E.A.R.S. Program

|

Editorial: By Mark Schiller Editorial: The Borrego Fire By Kay Matthews |

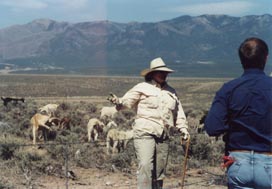

Send in the Goats: They'll Eat AnythingBy Kay MatthewsThe goats came down off the hills, all 600 of them, and trotted towards us, herded by their keeper, a single man with a staff. Some of them stopped and gave us a sniff, then hurried off to join their partners in a fenced off field of sagebrush, which they proceeded to eat. The sagebrush belongs to Tony Benson, a Taos rancher and board member of Taos Soil and Water Conservation District. The goats belong to Lani Lamming, who rents out her three herds of goats all over the west to get rid of noxious weeds on private ranches, along public highways, and on federal BLM and Forest Service lands.

The day began with a slide show and lecture by Lamming at the Agricultural Center in Taos, sponsored by the Quivira Coalition. Lamming, who has a master's degree in what she calls "weedology", is a Wyoming rancher who went into the goat business to combine her educational skills and her love of the ranching life. Unable to keep the family cattle ranch afloat, she and several of her children started raising goats and hiring them out to eat and kill the noxious weeds that plague our western lands as an alternative to chemical treatment. According to Lamming, a goat will first eat all the flowerheads off the weed and then go back and strip the leaves off the stalk, effectively killing the plant. They'll eat just about anything, including Leafy Spurge, a weed poisonous to cows they are so effective at land restoration projects in which the desired goal is to stimulate grass production. As they roam the land foraging for weeds they also leave their droppings as fertilizer and their hoof action breaks up the soil. Unlike cattle, they don't congregate in riparian areas (Lamming says they're like camels and don't need a lot of water) and have little impact on streamside vegetation. On the downside, however, Lamming warned that the goats like to eat cottonwoods as well as salt cedars and Russian olives so you might have to sacrifice some cottonwoods while you're getting rid of the invasive plants. But the herder can move the goats quickly out of the areas where they don't want them to linger. Besides herders, Lamming uses a combination of dogs and electric fences to control the movement of the goats. In the slides she showed a project in which she used fences in the lower elevations of the area, where the herders can more easily erect them, while the dogs kept the goats herded in the upper, less accessible areas of the project. As far as her sheepherders go, Lamming stressed that she likes to "de-stereotype us - we're intelligent, fun, and good looking. I pay well, and any college student or displaced rancher who already has animal handling skills, knows something about plants, and likes living in camp will find a good job with me." Lamming also showed slides of several other projects she and the goats have worked on over the last few years. She had just moved her goats from Leslie Barclay's ranch in the Galisteo Basin, where the herd had been grazing in the dormant season to get rid of Russian olives and salt cedars as well as stabilize the arroyos by rounding off the sharp edges with their hoof action. On a previous project in Santa Fe, the goats were able to eat weeds along the acequias instead of having to bring in machines that destabilize the ditchbanks. On a project in Colorado Springs her goats participated in a Christmas tree pilot project at the community organic garden, where people brought their discarded trees for the goats to eat on site, leaving their fertilizer for the organic gardeners. Next door to the community garden, in Bear Creek Park, the city had previously sprayed to get rid of thistle and ended up getting another invader in its place, teasel (and contaminating the organic garden with the chemicals from the spraying). Lamming grazed the park twice a year, starting in 1999 for three years, and by 2001 her slides showed a beautiful park full of grass and people. A novel idea that Lamming discussed at her lecture was using goats to bond with calves so that the calves would adopt some of the goats' behavior patterns, particularly not congregating in riparian areas. The cattle could help keep predators away and cut down on fencing needs. Lanning uses Cashmere goats because of their relatively small size, their gentle disposition, and the fact that as a byproduct they provide cashmere, which they shed in May and sells for $15 an ounce. She had some sweaters made from her goats' fir on display at the center, which came in black, brown and white goat colors and were incredibly soft and luxuriant. She told the groups of ranchers, environmentalists, and government agency people at her talk that it takes about a year to train the goats, and she keeps them for as long as she can. They are pretty much disease-free; the sage they eat acts as a natural wormer, and they build up immunities because of a stress-free life grazing on healthy land and a diverse diet. During the question and answer period Lamming was asked how she prices a project. She learned the hard way at first by bidding on the number of acres per project and losing up to $50,000 before she devised her current system of a bid based on per head/per day, which includes trained personnel, transportation (she contracts with truckers to haul the herds), and water. For a herd of 500 she charges one dollar per goat per day. The price goes down to 50 cents per day if the goats stay on site for more than a month. Tony Benson was unsure how long the goats would stay on his ranch, but they already had their next gig lined up: the highway department contracted with Lamming to use the goats for weed control because of citizens' objections to using chemical sprays. Perhaps the goats can also be used in the partnership Benson has established with several of his neighbors and the BLM on land restoration on Taos Mesa. You can contact Lamming at 307-421-3737 or call the Quivira Coalition at 505-820-2544. ANNOUNCEMENTS• On June18 the Embudo Valley Library is hosting a meeting for area residents to come and share their ideas about future expansion of facilities and services at the new library location in Dixon. Everyone is encouraged to attend so that future plans reflect the desires of the community. A time and place had yet to be determined at press time, but you may call the library at 579-9181 for further information. • The summer session at EcoVersity, Sustainable Living/Place-Based Learning, begins June 17th. If you register by June 10th you will receive a $10.00 discount per class. This summer's offerings include: Permaculture Basics; Drought Gardening; Soaring Crane QI Gong; Poetics of Place; Anasazi Farming, Gardening, and Water Harvesting; Mushroom Growing for Home Use; and several camping excursion classes to learn about high mountain herbs and Chaco Canyon. You may register on-line at: www.ecoversity.org; by e-mail: info@ecoversity.org; by phone: 505-424-9797; by mail: EcoVersity, Attn: Registrar, 2639 Agua Fria, Santa Fe, NM 87505; or by walk-in, one hour prior to first class.

|

Editorial:By Mark SchillerSome thoughts on the effects of the drought Over the next six months (unless we're baled out by significant rainfall) the general public in New Mexico and norteño water rights holders in particular are probably going to experience what it feels like to be cannon fodder in the battle to determine what the priorities are going to be with regard to water distribution during times of drought.The law of "prior appropriation," by which New Mexico water is supposedly distributed, states that the oldest established rights are entitled to their full appropriation before junior water rights are entitled to any appropriation Nonetheless, municipalities such as Santa Fe, Las Vegas, and Albuquerque, most of whose water rights are not very old, seem to think they have an inalienable right to enough water to not only sustain themselves but to continue to issue building permits which will further tax the dwindling water supply. Moreover, the State Engineer, Tom Turney, continues to assure these municipalities that he will not cut them off as long as they make a good faith effort to implement and enforce conservation measures for current residents. Why isn't the state engineer demanding that these cities place a moratorium (as Española has done) on building permits until the drought has subsided and long term, equitable regional water planning is in place? Why doesn't the state engineer demand that water guzzlers like Intel implement conservation measures? Why does the state engineer allow Albuquerque, the state's largest water user, to actually increase its water use during this crisis? Why does the state engineer allow a luxury subdevelopment like Las Campanas west of Santa Fe to actually increase its already outrageous water use during the drought, including millions of gallons of water for two 18 hole golf courses? The answer to all of the above is, of course, "money talks." Ironically, some of the poorest, most politically marginalized people in the state, the pueblos and the acequia communities of el norte, hold a substantial amount of the senior water rights. Norteños should be aware, however, that the state engineer, the developers and many of our state legislators are doing everything in their power to make it easier to transfer water out of agricultural use and into residential and commercial use. This includes: fighting legislation that would provide notification of proposed water transfers to acequia commissions so that they are able to protest the transfer within the prescribed period; endorsing erroneous and misleading reports such as the Western States Water Policy Report which states that agricultural uses of water are "lower value" and that if western states want to continue to prosper economically they must transfer water out of agricultural use and into "higher value" uses such as residential and commercial development; and continuing to allocate state moneys to buy up and retire agricultural water rights so that New Mexico can meet its interstate water delivery obligations. We are all well aware (or should be) of how the state and federal governments cheated the Native American and Hispanic communities out of their land grants. I suspect we'll see the same kind of unscrupulous tactics in their efforts to strip them of their water rights. Rural communities need to seize this opportunity to strengthen possibilities for economic development by retaining their increasingly valuable water rights and putting them to "value added" uses. Perhaps strategically situated communities such as La Cienega, just south of Santa Fe, need to take the "bull" by the horns and set a precedent for rural communities throughout the state. In letters to the editor of The New Mexican and The Journal North, members of that community have claimed that Santa Fe's "junior" water right use has impaired their "senior" surface and groundwater rights as well as drying up the wetlands for which the village was named. Now may be the time for them to seek a judicial remedy that will supercede the State Engineer's authority and prevent Santa Fe from using water to which La Cienega is entitled. New Mexico is one of the poorest states in the country. The gap between the rich and poor increases each year. The state must learn to live within its "carrying capacity" and stop allowing special interests to widen that gap by victimizing the poor. The National Fire Plan In response to my editorial in last month's La Jicarita about the National Fire Plan, I received a fax from Senator Bingaman's office that included a letter the senator wrote on May 7 to Forest Service Chief Dale Bosworth. In that letter the senator spoke about the dangerous conditions which exist in the Santa Fe Watershed and requested an additional $400,000 for this year so that the Forest Service can complete 1,000 acres of thinning rather than the 400 acres that have been targeted. He also asked Senator Robert Byrd, chairman of the Appropriations Subcommittee on Interior to help him secure $1.5 million for the Santa Fe Watershed Restoration project for 2003. While the additional money would be a step in the right direction, it's still not nearly enough to keep up with mounting danger of catastrophic wildfire in the watershed, never mind the rest of the state. Furthermore, why is the Forest Service discontinuing all thinning work during the forest closure? Doesn't it make sense to use some of the new equipment and manpower the Forest Service has been able to obtain with National Fire Plan dollars to continue the work at this critical time? I personally am not aware of a single instance in which chainsaw use has sparked a forest fire, but if that's the reason they are not continuing the thinning, wouldn't having pumper trucks and firefighters on sight afford enough protection to continue the work? The complete closure of these forests is also driving many community foresters with thinning contracts on national forests to the brink of bankruptcy. Does it make sense to use National Fire Plan dollars to fund these groups to buy equipment and create community capacity to do restoration work and then shut them out of the forest at the height of the fire season? Editorial: The Borrego FireBy Kay MatthewsI saw the smoke from what was soon named the Borrego Fire as I left Santa Fe on Wednesday, May 22, around 3:00 p.m. I knew immediately that it must be in the mountains near my home in El Valle, but I couldn't tell how far north it was until I reached the turnoff on SH 503 to Chimayó. I could see then that it was above the village of Cundiyó, in the piñon-juniper of Santa Fe National Forest. My beating heart calmed a little, but by the time I reached SH 76 above Córdova, around 3:45, and pulled off the road with other onlookers to watch the blaze jump from tree to tree in a crown fire, I knew that it could easily reach the upper mountain villages. Although it was unlikely that it would reach Córdova, which lay to the west of the fire being pushed northeast by the winds, Truchas was easily in the line of fire, and perhaps Ojo Sarco, Las Trampas, El Valle, Ojito, Chamisal, and Peñasco as well. The villages were spared, due to prevailing southwest winds which pushed the fire through the Santa Fe Forest and Truchas Land Grant into the Pecos Wilderness towards Carson National Forest. The heroic efforts of helicopter and airplane tanker pilots, who dropped hundreds of loads of water and chemical retardant along the perimeter of the fire helped prevent it from moving north, towards the communities. Ground crews then moved in to put out hotspots and secure more perimeter boundaries by establishing firebreaks. At a community meeting in Peñasco on Friday night, Carson National Forest fire officials sought to reassure residents that, assuming the winds continued to blow in their typical pattern, we were not in any imminent danger from the fire but would be dealing with residual smoke "until it rained." They also answered questions, and I asked what criteria the Forest Service uses when deciding what kind of attack to make against fires when conditions are as extreme as they are in this time of drought. We were told that that decision is made by the fire boss of the crew that makes the initial attack on the fire, but that Carson officials were "ready to bring in whatever resources are necessary." When I was watching the Borrego Fire burn for an hour and a half from my vantage point above Córdova, I wondered if the air tankers were on their way, or if the Forest Service knew how serious this fire already was. The agency is caught in a Catch 22 situation. Although it recognizes that a hundred years of fire suppression have left our forests densely stocked with small-diameter trees, it continues to suppress almost all fire because of the danger of catastrophic burns like the Borrego, Cerro Grande, and Viveash fires. Adding to the dilemma is the recent closure of New Mexico's forests because of drought conditions, which shuts down restoration projects that thin the densely stocked trees to prepare them for prescribed burns which will help prevent catastrophic fires. Ironically, the only method by which the forests are now treated is out-of-control fires which burn everything in their path, not just the underbrush and dog-hair thickets that need to be cleared. While this may be the scenario that some environmentalists have endorsed as the "natural" way to regenerate our forests, there are too many variables and disastrous possibilities for the rest of us to feel comfortable with this method. Is there a solution to this dilemma? In his editorial on page 4 Mark suggests that some of the restoration projects be allowed to continue with careful monitoring by Forest Service fire personnel. We are falling farther and farther behind in the critical wildland/urban interface projects designed to protect our communities. When he suggested to one of the local rangers that the Forest Service consider this option, her response was that the agency would then be violating its own regulations. That's the same kind of thinking that keeps us from examining ways to adjust the Endangered Species Act to allow for the flexibility to protect the needs of both people and habitat in a more integrated way. Unfortunately, the amount of restoration work needed to rectify conditions that result in fires like the Borrego is going to take many years and many millions of dollars to complete, and questions remain about the effectiveness of that work. Hopefully, once we can get into the Borrego Fire to see how effectively areas that were previously thinned and burned were able to slow down the fire, we can use this information to better plan our restoration efforts. But if we don't get busy soon we're going to end up using all the National Fire Plan monies to fight fires rather than prevent them. The Embudo Valley Celebrates Opening of New Library

Over 200 people celebrated the opening of the Embudo Valley Library in its new building in Dixon on Saturday, May 25. It was a multi-cultural event with food, a flamenco performance, and dancing to live music. With funding from an anonymous donor the community was able to purchase a house owned by the Zeller family, next door to the former Zeller's store. The house provides a beautiful, bright, and cheerful environment for the library, with room to expand library facilities onto the adjacent land. There will be a meeting on June 18 for community members to get together and discuss ideas for expanding the library facility and services. Everyone in the area is encouraged to attend. For information regarding the time and place of the meeting call: 579-9181. |

Home | Current Issue | Subscribe | About Us | Environmental Justice | Links | Archive | Index

Copyright 1996-2002 La Jicarita Box 6 El Valle Route, Chamisal, New Mexico 87521.