|

|

|

Volume VIII |

July/August 2003 |

Number VII |

|

|

Maude Barlow, Author of "Blue Gold, the Fight to Stop the Corporate Theft of the World's Water," Comes to Santa Fe By Kay Matthews Wool Traditions: A Fundraising EffortEditorial: Forest Terrorism By Mark Schiller |

Editorial: Bring Back Our Plazas By Kay Matthews Puntos de Vista: Have You Ever Fought a Landfill? By Deborah Begel |

Maude Barlow, Author of "Blue Gold, the Fight to Stop the Corporate Theft of the World's Water," Comes to Santa FeBy Kay MatthewsAt a July meeting with New Mexico community activists, Canadian author Maude Barlow got an earful about the water issues we face here: the silvery minnow lawsuit and the Endangered Species Act; tribal issues; the urban/rural conflict over transfers of water; and the commodification and privitization of this precious resource. Barlow is all too familiar with the latter issue: As a member of the The Council of Canadians, a nonprofit organization that came together to fight the Canadian-United States trade agreement, and author of Blue Gold, The Fight to Stop the Corporate Theft of the World's Water, she has been at the forefront of a united fight against corporate privitization of water resources.

In Santa Fe to deliver an address at the Armory for the Arts, Barlow met with the activists as part of the E.R.O.S. (Encouraging Relationships of Sustainability) speaker series, set up by family practitioners Leah Morton and Bruce Gollub. The meeting was an opportunity for local activists to learn about the global water issues Barlow has been involved with, to educate her about water issues specific to New Mexico, and to collaborate on strategies and a vision for these global and local battles. Barlow began her remarks by saying, "New Mexico is going to be a testing ground for the First World in the privitization and globalization of water. There are going to be divisions within the state as communities, such as the indigenous community, must make decisions about whether they want to sell their water." She also pointed out the dichotomy between the folks who live in "those big houses I saw in Albuquerque and Santa Fe who are in a state of denial" and the acequia system that "should be a model." Like other communities around the world we face daunting issues: the consequences of polluting our surface water and mining our ground water at an unsustainable rate; looking for a technological fix to water scarcity rather than employing conservation methods; and the increasing corporatization and privatization of water resources, aided and abetted by the World Trade Organization and The World Bank. She asked everyone, as the discussion began, to think about the basic principle she endorses as the solution to water sustainability: Conservation and Equity, conserving our water resources in a socially and economically equitable way. David Benavides, water attorney with New Mexico Legal Aid, moderated the meeting, presenting a list of topics that community activists wanted to discuss with Barlow. First on the list was the recent Federal Appeals Court decision upholding the Bureau of Reclamation's right to release any water necessary to sustain the silvery minnow in the Rio Grande, including diverted San Juan/Chama water that is owned by local cities and irrigation districts. Deb Hibbard, of Rio Grande Restoration, who introduced herself as a "non-minnowist", claimed that the fish has become a scapegoat for mismanagement of the Rio Grande and that the real issue is how do we protect the environment as well as rural/urban values: "Please ask Congress not to change the Endangered Species Act." She pointed out the city of Albuquerque's abysmal failure to implement meaningful water conservation during the drought. Roberto Mondragon, of Aspectos Culturales, responded to Hibbard's comments by calling himself a "peopleist" when it comes to the concerns of rural communities, and that conflicts with environmental groups are not over if they continue to go to court, as in the silvery minnow case, rather than dialogue with the farmers and ranchers who are dependent upon the Rio Grande for irrigation: "The Endangered Species Act needs to be amended to include rural community members as endangered species," Mondragon said. As others joined in the discussion, it was clear that there remains distrust and conflict between those activists who represent environmental groups like Rio Grande Restoration and those from the rural farming and ranching community. Paula Garcia, director of the New Mexico Acequia Association, put the conflict into historical context: Rural Hispano parciantes are living with the legal reality of a colonially imposed system of private property rights, and the Endangered Species Act is seen as an overarching threat to those who have priority water rights."When people feel insecure about their rights its hard for them to focus on their conservation," she said. Barlow responded to the dialogue by stressing again the basic principle of Conservation and Equity and that we need to distinguish between traditional private property rights and the commodification of water rights for profit. As another participant had previously pointed out, corporations love the divisions between environmentalists and rural people because it opens the door for their efforts to buy and sell water on the open market. Barlow cautioned that "People in this room have to come together if we want to bring these corporate behemoths down." The next topic of discussion was tribal issues related to market issues. Barlow presented an overview of Canadian indigenous issues, which are similar to those in this country: economic deprivation; divided pueblos and tribes; and outside pressure to buy into an economic system that has already subverted culture and destroyed resources. Richard Deertrack of Taos Pueblo spoke of the 50-60% unemployment rate on New Mexico pueblos: "I can understand why tribes engage in economic enterprises or sell out to a hydroelectric project or whatever." Don Bustos, Santa Cruz farmer and president of the board of the Santa Fe Farmers' Market said that the same thing is true for the Hispano community of northern New Mexico: "Water conservation is useless until there is economic equity." John Brown, executive director of the New Mexico Water Dialogue, initiated a discussion of how a state like New Mexico can recreate the direct democracy of acequias in our urban areas, where water use is considered private but the resource is a common one. How can allocation decisions be made without leaving it to market forces, and who is empowered to make them? Barlow agreed that we have a unique and complicated situation with regard to water rights and appropriative use, but the acequia system may help us prevent a worldwide trend where corporations impose urban water systems on rural communities. We must use the example of acequia democracy to establish a different kind of urban water system that uses appropriate technology and self reliance and promotes social justice and equity. Further discussion centered around the tension between rural and urban communities, with urban environmentalists accusing the agricultural communities of wasteful irrigation practices and farmers and ranchers accusing cities of failing to implement limits on growth and development. Again, it is an issue of economic equity: by supporting local economies like small wood mills and farmers' markets, urban residents can contain corporate development and recycle money throughout the state. As Don Bustos and Paula Garcia pointed out, farmers and ranchers can use appropriate conservation methods only when they are confident that their water rights will not be transferred to "higher and better uses" (i.e., urban and industrial) and the beneficiary of that conservation is their communities. Barlow ended the discussion with a summation of the ten principles she believes will help protect our water resources: 1. Water belongs to the earth and all species. 2. Water should be left where it is wherever possible. 3. Water must be conserved for all time. 4. Polluted water must be reclaimed. 5. Water is best protected in natural watersheds. 6. Water is a public trust to be guarded at all levels of government. 7. Access to an adequate supply of clean water is a basic human right. 8. The best advocates for water are local communities and citizens. 9. The public must participate as an equal partner with government to protect water. 10. Economic globalization policies are not water sustainable. Wool Traditions: A Fundraising EffortWith a $40,000 anonymous donation in hand, Wool Traditions, a recently formed Taos non-profit, is looking for a home: a place where every facet of producing weavings &emdash; from grazing sheep to dying wool to selling blankets &emdash; can demonstrate the viability of one of the area's longest lived traditions and sustainable businesses. The organization is currently negotiating on two properties, but, according to Robin Collier, executive director, the group needs to raise more money for a final purchase. They are also interested in hearing about other possible locations (and a temporary rental location for natural dye and retail operations). Collier can be reached at 751-1987. Meanwhile, they have made substantial progress in the getting the various components of the operation up and running. They recently washed 28,000 pounds of Rambouillet and Churro wool in their first organic wash, including large amounts of black and grey wool. Working with Bolivian agronomist and bio-dynamic herbalist José Emigdio Ballon, they are developing dye plants and herbal pharmaceuticals such as cota (with anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties that produces orange dyes) and Yerba de la Negrita (which produces an ivory dye and is used as an herbal hair rinse). On-line purchases of native and exotic dye plants and extracts can be made on the organization's web site: www.organicyarn.com. They also recently purchased a 120 spindle woolen spinning mill from the Pedro P. Trujillo family in Chamita. They will start spinning Rambouillet and Churro yarn at the Chamita location with Pete's instruction. They hope to soon offer very competitively priced yarn from local wool for local weavers. And finally, in an effort to raise awareness of the importance of acequias, the group has been invited to submit a proposal to the McCune Charitable Foundation to train area youth to document acequias with photos, text, and sound to present to the community. ANNOUNCEMENTS• The New Mexico Organic Commodity Commission announces a new two-year (June 1, 2003 through September 30, 2004) program to reimburse farmers 75% of the cost of organic certification (up to $500/year). According to Commission Director Erica Peters, "Farmers in New Mexico pay anything from $150 to thousands of dollars for organic certification." They should call the New Mexico Organic Commodity Commission at 505 266-9849 to find out more about organic certification and the cost-share program. • The New Mexico Environmental Law Center will be celebrating its sixteenth anniversary on Sunday, September 14, 2003 from 3-5 pm at the Hyde Park Lodge in Santa Fe. The event will also include the law center's annual environmental awards ceremony. For more information you may contact the center at www.nmenvirolaw.org, 989-9022. • The Forest Service is soliciting additional input on the proposed Ojo Caliente 115 kV Transmission Line before the Draft Environmental Impact Statement is released in August. The plan was first released to the public for comment in March of 2000 but was temporarily delayed. The proposed line would run from the existing 115 kV and 345kV transmission corridor operated by Tri State Electric to the Ojo Caliente area. The project also includes construction of a substation on Bureau of Land Management Lands north of State Road 111 in the Ojo Caliente area. The proposed alternatives include: No Action; the Proposed Action, which would tap into the existing 115kV line north of Black Mesa and proceed north and west to connect into the existing 25kV distribution corridor; using the Existing Location northeast of the community of Carson to follow the existing route along the sough side of US 285 to the proposed substation; Route 285 P, which would mitigate impacts on visual/scenic quality by routing the line along Forest Road 285 P to US 285; and the Tres Piedras Connection Option, which would provide electrical service to Cerro Mojino near Tres Piedras and could be added to any of the other alternatives. For further information, contact Larry Cisneros at Kit Carson Electric Coop, 758-2258, ext. 136, or to comment on the project contact Carson National Forest, 208 Cruz Alta Rd., Taos, NM 87571 or call Ben Kuykendall, Team Leader, at 758-6311. • The Rio Grande/Rio Bravo Basin Coalition announces the commemoration of Dia del Rio on October 18, 2003. This is a celebration that brings inhabitants of the basin together in a common cause. Individuals, organizations, and institutions from all sectors join together to peacefully, constructively, and actively work around a specific problem that needs a solution. Grants from the Coalition were dispersed in July to help member organizations with specific projects. For more information call the US office at 915 532-0399 or e-mail at coalition@rioweb.org. Editorial: Forest TerrorismBy Mark SchillerThe July 12 edition of the Albuquerque Journal contained an article from the Associated Press claiming the FBI alerted law enforcement agencies throughout the west "that an al-Qaida terrorist now in detention had talked of masterminding a plot to set a series of devastating forest fires around the western United States." I can't help but think that if this is truly the case, Al-Qaida intelligence sources are even more incompetent than the sources from whom George W. Bush gathered intelligence about Iraq's "Weapons of Mass Destruction." Surely, if al-Qaida strategists bothered to read the paper they would realize that Congress and the Forest Service, through their negligence and incompetence, have already created an environment that will inevitably lead to more catastrophic fires. You don't have to look any further than the recent Capulin and Molina fires in the Pecos Wilderness north of Santa Fe.for evidence of this. Despite the fact that agency officials had been alerted that fuel moisture levels are at an all time low and that there are tens of thousands of highly combustible standing dead trees recently killed by the combination of drought and beetle infestation, Forest Service officials made the decision to allow these two fires, which were caused by lightning strikes on June 23, to burn. While I understand the need to reintroduce fire as a forest rehabilitation tool (after years of Forest Service and Congressional mismanagement, which is the main cause of the current unhealthy conditions), it doesn't take a rocket scientist to realize you are running an enormous risk of catastrophic fire if you don't suppress these natural fires until the summer monsoons have an opportunity to raise moisture levels. If the Forest Service had gotten on these fires immediately they probably could have been kept to less than 200 acres and the costs and side effects would have been minimal. Instead, they allowed them get out of control. The fires consumed approximately 7,200 acres, involved hundreds of firefighters and five helicopter crews, burned sacred sites and culturally sensitive areas on the Nambe Pueblo Grant, and caused severe smoke inhalation problems for communities from Santa Fe to Peñasco. They still threaten to pollute the Pueblo's watershed with ash and silt and poison the fish in its lake if the summer monsoons ever materialize The bill for all this will be enormous. Could al-Qaida have orchestrated a more devious scenario? Which brings me to my final concern: Has al-Qaida already infiltrated the ranks of the Forest Service? In some ways it would be a reassuring explanation for many of the decisions the Forest Service has made recently. Instead of simply accusing the agency of gross incompetence, inability to communicate among themselves and with the public, and a total absence of accountability which its actions (or lack thereof) would otherwise warrant, let's just blame it on "the axis of evil." There, I feel better already. |

Editorial: Bring Back Our PlazasBy Kay MatthewsThe day after I came home from a trip to Oaxaca City, Mexico, The Taos News ran an editorial endorsing the efforts of Taoseños (organized as the Taos Project) to rejuvenate the Plaza. The editorial listed some of the topics the Project hopes to address: automobile traffic, congestion, and parking; scarcity of bathroom facilities; beautification and cleanliness; lighting and signage. In Santa Fe, the main topic of debate concerning its plaza has been whether to close it to traffic. While these are all issues that need to be dealt with if we want to bring back some kind of life to our sterile plazas, this alone isn't going to make them real Zocolos again. Because what that requires, as I saw in Oaxaca, is a community whose heart is the Zocolo. And I'm afraid we long ago lost the defining qualities that Oaxaca still retains: a community where all economic and ethnic populations rub shoulders in the streets, where people actually walk through a central district of offices, shops, churches, government buildings, and restaurants, where all services &emdash; cambios, banks, liquor stores, farmacias, clothing stores, and cafes &emdash;meet the needs of the locals and tourists alike. The Zocolo is a microcosm of all of this, where everyone gathers to watch the human parade, where stalls serve indigenous Indio and Mexicano food and venders sell crafts ranging in price from a few pesos for a black pottery chicken to a thousand peso huipil, where every celebration and observance, both secular and religious, fills the square with participants and observers. On noche buena afternoon, hundreds of activists demonstrated against the incarceration of political prisoners, and that evening, twenty brilliantly lit trucks paraded through the Zocolo loaded down with children, goats, shepherds, manger tableaus, and church scenes that captivated a crowd ranging from the elegant Oaxaqueña with her toy poodle to the vendors taking a break from their work. This range also reveals the inequities of Mexican life, of course, which are ever present in the Zocolo: the impoverished Indians from the surrounding pueblos who come for a day's work to sell their food and crafts on the streets. If they make enough money for the day they can pay for a night's lodging. If not, they sleep on the street. The poverty is never hidden behind the trappings of tourism like it is here. In Oaxaca one sees life for what it is; here, in the Taos or Santa Fe plazas, we see only what the City Fathers want us to see. Although Taoseños recently won the fight against Super Wal-Mart coming to town, ironically enough, the current Wal-Mart, that omnipresent symbol of corporate globalization, functions as the Taos Zocolo. Wal-Mart is where we all run into each other, buying our school supplies and and dog food, and where we stop for a few minutes to visit and to gossip. Maybe we should forget about the plaza renovation, which sounds suspiciously like an expanded tourist trap anyway, and get Wal-Mart to bring in some taco stands and licuado bars to provide refreshment and some ranchera bands to provide entertainment and recreation. Then we can once again be part of an integrated community that talks, eats, sings, and dances together, even if all our money is going straight to corporate headquarters. Puntos de Vista: Have You Ever Fought a Landfill?By Deborah BegelView from the Mesa Up on the mesa, mountain peaks jut up from high mountain plains in at least three directions. Rancher Joe Martinez looks around at the land he knows so well. He has grazed his cattle here for over three decades. "I haven't heard from the BLM," he says. He's been worried since his last meeting, when officials warned him he might lose his grazing permits.  Rancher Joe Martinez has grazed his cattle on the mesa above Ojo Caliente for more than three decades. He says he and other villagers have come up on this land for years to enjoy it, have picnics, ride horses across this windy plain, gather medicinal herbs and watch the cranes fly by. Now it's a slated to be a dump. Have you ever fought a landfill? I have. I joined Joe and others in a a citizens group in December, 2002, when the North Central Solid Waste Authority (Española, Rio Arriba County, San Juan and Santa Clara Pueblos) held so-called "scoping" meetings to ram the dump down our throats. A Brief History The dump site is a vast open mesa beside U.S. Highway 285, which cuts a curvy ribbon between the mesa and the Rio Ojo Caliente Valley. The historic village of Ojo Caliente is in this valley. Our group, the Landfill Concerns Committee of Ojo Caliente, believes this dump site is a terrible choice. Consider the following: • Tens of thousands of Native Americans, from those who speak Tewa to those who speak Jicarilla Apache, were born, lived and died on this land. It is hallowed. Signs of daily life are abundant. Pottery shards are sprinkled across a wide swath of land. Remnants of grid gardens are visible. Some people say you can still trace the old roads that crossed this land. • Long after Native Americans moved away, Hispanics settled the Rio Ojo Caliente Valley in 1790. Those first 53 colonists were given the Ojo Caliente Land Grant, with 38,000 acres, much of it in common lands on the mesa. • Hundreds &emdash; or is it thousands? &emdash; of sandhill cranes fly over this river valley and the mesa every spring and fall. We hear them first, then look high in the sky to watch them flying in ever changing formations. Joe Martinez and other locals tell many tales of cranes stopping on the mesa to rest. • Traffic deaths. The Landfill Concerns Committee has counted more than a dozen traffic accident deaths on U.S. Highway 285 since the road was "improved" a couple of years ago. But we don't just count them. To us, the dead have names and faces. Even worse, the entrance to the proposed dump follows a curve where many people speed. A little girl, Amanda Sanchez, was killed by a truck there a few years ago when she crossed the highway to put out TRASH! Yes, trash.

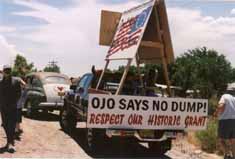

Tim Vierek painted signs for his float for the 4th of July parade this year in Ojo Caliente. His children, Raphaela and Jasper, ride in it. Danger and Risk • Air Pollution. We found a study that links air pollution near landfills to increased birth defects. This landfill is less than a mile from Ojo Caliente. • Water Pollution. The Waste Authority experts claim that if there's a leak in the landfill, the liquid would travel east, away from the village and the river valley. And of course it couldn't possibly harm the community well on the south side of town, a couple of stones' throws from the dump, could it? That's the well that didn't give out during the recent drought, by the way. To date, the Authority has only sent one bore into the ground on the mesa, so how could the experts be so sure our groundwater won't get polluted by leaks? Speaking of hazards, did you know that an average of one to two percent of the trash in landfills is hazardous? I'm talking about household cleaning products, Draino, motor oil and pesticides. Yes, GARBAGE-IS-US, but we do have the power to manage it so that it won't up and kill us or give our children cancer. Waste and trash expert Peter Montague told me, "All landfills eventually do leak." Mitigate, Mitigate The BLM is key to the Ojo site selection because the agency is the custodian of the 160 acres it plans to sell for $10 an acre (undervalued!) to the Authority. When we met with the BLM, they told us they can "mitigate" just about any obstacle. How do they do that? They take an action that they feel corrects for future damage. A couple of examples: • Endangered whooping cranes have been sighted by locals stopping on the mesa? No problem, the birds can land somewhere else. It's only a problem if they nest there. • The area is unexplored archeologically? No problem. "Bag it and tag it," the archeologists tell us. You just dig a trench and put the relics and pot shards into bags as you sift through the soil. One slice represents the whole. Still, we are not putting down the BLM folks in Taos. They listened when we told them the site selectors should have identified more than one possible dump location. The BLM sent Authority engineers back to square one.

Lisa and Eric Oppenheimer carry a banner in the 4th of July parade in Ojo Caliente. There's Money in Trash Rio Arriba County Manger Lorenzo Valdez has been keen on building a landfill since the idea first crept up about a decade ago. When one of our members, Betty Haagenstad, asked him what he liked about a dump, he said, "Betty, don't you know there's money in trash?" Of course we know that jobs are scarce in these parts. But why develop new sources of money that threaten peoples' health and welfare? Betty is a persistent questioner and researcher. She went to the Authority's own economic projections and found that with a small waste stream like ours, about 39,000 people, we're 3,000 people short of break-even. We can imagine the Waste Authority complaining in a couple years that it's losing money, begging for a permit to accept out of state trash and raise the danger level of the landfill permit. A Trashy Future That frightening thought leads us to a brighter future. Here's a one, two, three step plan for your consideration: Step one: We must all begin to separate our trash, sending recyclables, re-usables and renewables to their proper destinies. We may take inspiration from the late brave Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone, who said, "Never separate the lives you live from the words you speak." Step two: Let's send our waste authority on a tour of greener landfills so they may learn to turn our trash, sludge and sawdust into fertile soil. It's a return to old technology, composting. Step three: Tell our leaders how you feel about this landfill. Stand with us and demand that today's leaders do the following: • Work with a regional landfill to buy some time. • Study ways to separate out the valuable and the toxic trash. Develop solid education and enforcement plans with both rewards and punishments. • Begin negotiations and plans to compost our trash. Finally, a moral imperative. We must not pollute the earth for generations to come simply because it's cheaper and creates a few jobs. The decisions we make today are critical to the future health of generations of people who would like to live &emdash; and thrive &emdash; in Ojo Caliente. Updates on Forest Service Proposed Projects: Agua/Caballos, La Joya Wildland/Urban Interface, and Borrego SalvageCarson National Forest recently released a Supplement to the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the Agua/Caballos Proposed Projects. This is in response to an appeal filed with the Regional Forester of the Agua/Caballos Record of Decision that was signed on June 3, 2002. The appeal, filed by Joanie Berdie of Carson Forest Watch, Paul Becker of Vallecitos Stables, and John Horning of Forest Guardians, accused the Forest Service of failing to gather the necessary population data for indicator species in the Vallecitos Sustained Yield Unit as required by the National Forest Management Act (NFMA). (See the September/October issue of La Jicarita News.) The appeal was upheld by the Deputy Regional Forester, who directed the Carson to "complete the analysis of effects on management indicator species (MIS) considering population and habitat information collected at the forest plan level or at an appropriate geographical scale for a particular species." This analysis is included in the Supplemental FEIS, which is now released for public comment: the Forest Service is asking the public to comment only on the information in the supplemental document. The preferred alternative, identified in the FEIS, is still Alternative G. A new decision will be made after reviewing all of the comments. For more information you may call Kurt Winchester at 758-6310. Two areas around the village of La Joya on the Camino Real Ranger District will be thinned to reduce hazardous fuels under a Categorical Exclusion (therefore not subject to appeal). The district first proposed the project in December of 2002, and after several meeting with affected residents and interested agencies and organizations, adjusted the proposal based on their input: restricting access to green fuelwood removal; leaving a higher number of trees per acre in one of the units; and utilizing stewardship blocks as a method of thinning in the area closest to the community of La Joya. Under the new decision memo, Area A, consisting of approximately 134 acres, will be thinned to a stocking level of 80 to 150 trees per acre. Area B, consisting of approximately 154 acres, will be thinned to a stocking level of 120 to 150 trees per acre. In both areas, no trees over 12 inches in diameter will be cut. After thinning slash will be piles and/or broadcast burned. No new roads will be created. The Forest Service hopes to issue an appendix to the Borrego Salvage Project EA (released in April) that clarifies three areas of concern for this salvage sale of timber that burned in the Borrego fire of May, 2002: erosion potential; goshawk habitat stand density; and road inventory corrections. This release will constitute a Record of Decision, with an appeal period of 45 days. According to the Forest Service, it is unlikely that a contractor will begin work on the sale this year even if no appeal is filed.

We wish to express our condolences to all of Frances "Fiz" Harwood's friends and relatives. Fiz, who died Saturday, July 5, was a long-time norteño activist and generous supporter of La Jicarita News. She founded EcoVersity in 2001, a school dedicated to "hands-on experiential learning leading to real world problem solving." She was committed to helping maintain the culture and traditions of northern New Mexico: with one of her donations to the paper she wrote, "The school could use a course on land-based communities in northern New Mexico, a series of grassroots speakers and field trips to various projects in rural areas."As she said to us in her last letter we now say to her: "Many thanks for your good work." |

Home | Current Issue | Subscribe | About Us | Environmental Justice | Links | Archive | Index

Copyright 1996-2003 La Jicarita Box 6 El Valle Route, Chamisal, New Mexico 87521.