|

|

|

Volume XI |

December 2006 |

Number XI |

|

|

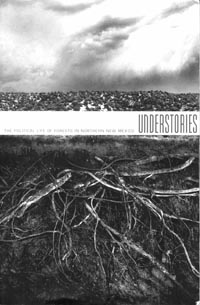

Book Review: Understories: The Political Life of Forests in Northern New Mexico By Jake Kosek Reviewed by Kay Matthews and Mark Schiller (Part One)ANNOUNCEMENTS |

Bechtel and Los Alamos National Laboratory: The Privatization of the Nuclear Industry By Kay Matthews Editorial: Politics as Usual in Rio Arriba County By Kay Matthews |

Book Review: Understories: The Political Life of Forests in Northern New Mexico By Jake KosekReviewed by Kay Matthews and Mark Schiller (Part One)UNM professor Jake Kosek's book, Understories: The Political Life of Forests in Northern New Mexico, is finally available at this critically important moment for those of us who were at the front lines of northern New Mexico's forest battles in the 1990s. The revisionist spin that Forest Guardians and other environmental groups has tried to put on this period (see the November issue of La Jicarita News) is thoroughly repudiated by Kosek's penetrating look at the roles these organizations played in el norte and their connection to an historical legacy of white privilege and exclusion.  While Kosek's book is on one level "our" story, the Max Córdovas, the Ike DeVargases, the Salomon Martinezes, and the Paula Montoyas, more importantly it is the story of what lies beneath ("Understories") the intense conflict that erupted over forest management in northern New Mexico. His book reveals that our battlefield was not just a site of struggle for access to and control of forest resources, but an "extraordinarily complex and incendiary site of deep personal passions, contradictory historical legacies, and intense social protest." It is the "story in which forest management, protection, exploitation, degradation, and restoration are inseparably tied to the social conflicts and cultural politics of race, class, and nation." Kosek explores four linked stories that form the core of his critique: 1) the forest's role in forming passionate attachments to place, community, and land; 2) the environmental movement's legacy of purity based on exclusion, nation, and race; 3) the ways in which the Forest Service's paternalistic role of "caring for the land and serving the people" institutionalizes its position and rule; and 4) the colonial and irradiating connection between Los Alamos National Laboratory, the forests, and the communities of el norte. Kosek begins by describing his arrival in Truchas to do field research for his Ph.D. dissertation in his Introduction: "I parked my truck and headed across some empty fields towards my new house. About 100 yards into my trek I heard the sharp report of rifle shot, followed instantly by the whiz of a bullet over my head. At first I thought it was a mistake, that he had mistaken me for something or someone else. But the second shot &endash; even closer than the first &endash; convinced me that it was not a mistake. Yelling at the top of his lungs in Spanish, he suggested that I had better 'fucking get [my] mother fucking white ass off the grant and out of [his] sight' or he was going to put 'a fucking hole in [my] head.' Pointing over my shoulder, I told him in Spanish that I was moving into the broken-down adobe house across the field, and that the road to it was flooded. He responded in English, asking 'How long do you want to live for?' Then he laughed and took another shot, this time hitting the ground about 10 feet away from where I was standing. After yelling at me some more, he went back into his house &endash; which turned out to be directly next to mine." This incident was a "material and symbolic" beginning: material, in that bullets and environmentalists hung in effigy during those days expressed the very real anger and frustration of the Hispano land grant communities who were once again being disenfranchised by outside colonial forces; and symbolically, in their attachment and sense of loss to land and community. Kosek devotes two chapters (the first and third) to examining the underpinnings of these sentiments of loss and longing by providing an historical, theoretical, and narrative context to the events that transpired. Chapter One, "Deep Roots and Long Shadows: The Cultural Politics of Memory and Longing," explores how "memories of dispossession and longing for land constitute Hispano identity and cohere Hispano community." Kosek provides the selective history necessary to contextualize this longing: Spanish colonial settlement; the 1846 American conquest and the resulting Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ("perhaps the most important document in the living history of Northern New Mexico"); and the loss of the land grants through corruption and swindle. As Kosek explains, however, the loss of the land grants has come to mean more than the Hispano's inability to make a living off the land: " . . . [the] struggle against forgetting is a struggle to maintain not just the possibility of justice in the future; the history of loss and sentiments of longing . . . have become the very glue that bind . . . a broader Hispanic community in Northern New Mexico." "With these memory claims come . . . powerful political possibilities" but they also reveal divisions and contradictions between Native American and Hispano communities. Kosek quotes Truchas activist Jerry Fuentes: "Do you want to know why things are so screwed up here [in Northern New Mexico]? . . . I will tell you. . . . We have got both the blood of the colonizer and the blood of the colonized in our veins . . . we are the conquerors and the conquered, the victors and the victims. . . ." Kosek illustrates these political yet divisive possibilities in his examination of the Alianza Federal de las Mercedes takeover of the Echo Creek Campground in 1966 and the 1999 "taking" of Juan de Oñate's foot from a statue at the Oñate Cultural Center in Alcalde. In Chapter Three, "Passionate Attachments and the Nature of Belonging," Kosek explores how norteño activists define their roles within the context of these sentiments in their battles with environmentalists like Forest Guardians and Forest Conservation Council. He compares the political perspectives of two pivotal norteño activists, Max Córdova of Truchas and Antonio "Ike" DeVargas of Vallecitos to explain how "the yoke between people and landscape continues to be a defining factor, an intrinsic characteristic and a natural tendency that binds race, nature, and place." Córdova, who led a protest at Borrego Mesa in 1995 defying a federal injunction on firewood removal, emphasizes the environmentalists' threat to the "traditional bond between people and place." As Kosek explains, Córdova "needed to articulate this protest in the realm of this traditional sense of belonging. He discussed the bond between people and forest in general, and Borrego Mesa in particular, employing the language of property rights and using the metaphor of 'the fingers on my hand.'" Ike DeVargas, while he attended the Borrego Mesa demonstration, later in 1995 helped organize a protest in Santa Fe, during which environmentalists were hung in effigy. In contract to Córdova's focus on belonging, DeVargas' "interest in the forest is related less to an idealized traditional cultural bond and more to issues of social and environmental justice." The protest "this time centered not around . . . traditional ties to the land but around rights, jobs, race, and poverty. . . . The protest was widely criticized in the press for being too extreme and violent. It also afforded the environmentalists an opportunity to regalvanize some 'liberal sentiment' on their own behalf by portraying the protestors as violent, angry radicals." Kosek explains that DeVargas' cross-cultural commitment to people who labor in the forests ultimately worked against him because environmentalists asserted "that this movement was no longer driven by traditional villages with cultural bonds but rather by angry workers who were a front for corporate interests. . . . Whereas environmentalists' sentiments of belonging derive from notions about nature, Hispanos sentiments derive from notions about labor. The conflict between the two materializes when both are seeking purchase on the same ground." This sets the stage for Kosek's analysis of the roots of the environmental movement in Chapter Four, "Racial Degradation and Environmental Anxieties." Kosek posits that the biocentric environmentalism (or environmentalism sin gente) advocated by Forest Guardians and other absolutist environmental groups, has its origins in the notion of purity, closely associated with the racial purity of the eugenics movement. "Most often, the history of the environmental movement is traced to abusive land practices at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, greater scientific understanding of 'natural' processes, or the rise and expansion of modern 'enlightened' thinking into nonhuman realms. Progressive critiques ofcapitalism have become part of some wilderness advocates' rationale for the protection of 'wild' spaces. These histories have clearly contributed to the development of the wilderness movement, but current battles within it point to a still greater diversity of origins. From among those, I call into view an estranged ancestor: the movement for white racial purity, a specter of environmentalism's past that is hardly acknowledged yet never entirely absent. As others have pointed out, while wilderness is a concept that by definition runs counter to modernity and politics, it is, in truth, a product of both. It carries with it complicated inheritances that counter its own claims to timelessness and universality. One need only look at the eviction of Native Americans from such icons of wild America as Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Glacier National Park (among others) to understand the deep and material contradictions of claims to pure, untouched nature." Starting with the nineteenth century policy of "manifest destiny" that asserted the racial and moral superiority of Anglo America and promulgated the theory that the American people had a pre-emptive right to the entire north American continent, New Mexicans have been directly affected by these notions of purity. Kosek traces the history of this movement from Francis Galton, who "coined the term 'eugenics' &endash; meaning 'good in birth' . . . ." to American advocates of selective breeding, immigration restrictions, sterilization programs, marriage laws, health policies, and segregation programs that included early environmentalists John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and George Perkins Marsh (the latter two were pivotal in helping create and guide the Forest Service). Their "writings were often explicitly racist . . . and their impulse to create and protect national wilderness areas flowed directly from the perceived need to differentiate and protect the 'pure' from the 'polluted,' the 'natural,' from the 'unnatural.'" Kosek brings these histories of "purity and pollution, blood and soil, body and nation" back to the struggles over northern New Mexico's forests at the end of the chapter when he describes Forest Guardians' 1999 Earth Day presentation at the Santa Fe Public Library. In an attempt to spin a revisionist account of the origins of the environmental movement, Forest Guardian Bryan Bird suggested to the crowd, "It was the civil rights movement activists in the 1960s and their discovering the words of Muir and Leopold that launched the modern day environmental movement." Bird then unwittingly went on to reveal the real basis of his environmentalism when he discussed Forest Guardians' campaign against logging in the Vallecitos Sustained Yield Unit: "The dangers to this area are real; what lies in the balance is the last best hope for the preservation of one of the few remaining unspoiled areas of forest in the region." Kosek notes that "The talk ended with a call not to compromise the last free and wild places in the West and the commitment to 'rewilding' the West . . . ." In point of fact, of course, the Hispanos of the communities surrounding the Sustained Yield Unit already had a long and intimate relationship with the area and years before Forest Guardians arrived had argued with the Forest Service to reduce timber sales, close roads, restrict future road building, and design a management plan that accounted for the needs of wildlife habitat. It is these same people that Forest Guardians accused of exploiting forest resources and "degrading" the environment. Unfortunately, due to space constraints we must end here, but we'll finish our review of Kosek's book in next month's La Jicarita, continuing with his discussion of race and nation in his chapter on Smokey Bear, and on the two stories we mentioned previously: the ways in which the Forest Service institutionalizes its position and rule; and the colonial and irradiating connection between Los Alamos National Laboratory, the forests, and the communities of el norte. Kosek will be scheduling book signings in both Albuquerque and Santa Fe after the first of the year and we will include them in our Announcements section in January. ANNOUNCEMENTS• The Quivira Coalition's Sixth Annual Conference, "Fresh Eyes on the Land: Innovation and the Next Generation", will be held in Albuquerque from Thursday through Saturday, January 18-20, 2007. This year the famed author and agrarianist Wendell Berry will kick off the activities with an informal evening of dialogue on Thursday night. The conference will be held at the Marriott Albuquerque Pyramid North, located at 5151 San Francisco Road NE off Interstate 25 in the Journal Center Business Complex. The conference fee is $85 for Quivira Coalition members and $110 for non-members; a special student rate is $35. You can register online at www.quiviracoalition.org or by mail to The Quivira Coalition, 1413 Second Street, Suite 1, Santa Fe, NM, 87505 (register by January 10 to avoid a late fee). • The New Mexico Organic Farming Conference will be held in Albuquerque on Friday and Saturday, February 16-17, 2007, 7:30 am to 5:00 pm. Conference organizers include Farm to Table, the New Mexico Department of Agriculture, the New Mexico Organic Commodity Commission, and the New Mexico University Cooperative Extension Service. The conference keynote speaker will be Miguel Altieri, Associate Professor at UC Berkeley who developed the concept of "agroecology", which respects the knowledge of indigenous peoples, protects the environment, and promotes social equality.The conference will be held at the Marriott Albuquerque Pyramid North, located at 5151 San Francisco Road NE off Interstate 25 in the Journal Center Business Complex. Registration for both days is $100 and $65 for either Friday or Saturday. For more information contact Le Adams at 505 473-1004 or Joanie Quinn at 505 841-9067 or send your registration to Farm to Table, 3900 Paseo del Sol, Santa Fe, NM 87507. • Next month's La Jicarita News will include an article detailing "Complex 2030" (popularly known as Bombplex), the National Nuclear Security Administration's proposal to consolidate and expand nuclear weapon's production. One of the sights being considered for this project is Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). The Department of Energy is soliciting input from the public concerning its proposed alternatives, which include: 1) no action or maintaining the status quo; 2) transforming to a "responsive" nuclear weapons complex (obviously the preferred alternative); and 3) a reduced operations capability complex. Many speakers at the Santa Fe scoping meeting pointed out the obvious shortcomings of these alternatives: there is no disarmament alternative and the United States has never been in compliance with the "Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty" (NPT), which it signed more than 35 years ago. Moreover, the scoping process itself is a sham. While we believe that the government is only soliciting input to be in compliance with its own regulations, we urge readers to submit their comments, but more importantly, to contact Senator Jeff Bingaman, who will be the new head of the Senate Energy Committee (1-800-443-8658, senator_bingaman@bingaman.senate.gov) and demand that the United States comply with the NPT, dismantle its entire nuclear weapons stockpile and focus facilities such as LANL on finding solutions to energy, medical, and social problems.

|

Bechtel and Los Alamos National Laboratory: The Privatization of the Nuclear IndustryBy Kay MatthewsThe Bechtel/University of California consortium now managing Los Alamos National Laboratory wasted no time revealing what privatization will bring to the Lab: the impending layoff of 450 to 600 contract workers, and a subsequent reduction in the work force &endash; through attrition &endash; of another 300, is testimony to its "cost-efficient" path towards profit. Of course, Bechtel itself is guaranteed a contractual amount of profit, no matter what it has to do to meet a Department of Energy (DOE) budget. And Bechtel excels in making a profit: in 2004 the company had revenues of $17.4 billion and 2005, $18.1 billion. As Steve Bechtel Sr., son of Bechtel founder Warren Bechtel and father of current CEO Steve Bechtel Jr., put it, "We are not in the construction and engineering business. We are in the business of making money." (Layton McCartney, Friends in High Places, 1988.) To better understand what Bechtel management of the Lab may mean it's useful to take a look at the company's history. Founded by Californian Warren Bechtel in the early 1900s, Bechtel took advantage of the rebuilding opportunities after the San Francisco Earthquake and initially specialized in railroad and irrigation canal construction. The company also branched out into mining, insurance, real estate development, highway construction, and oil pipeline construction, and by the end of the 1920s Bechtel was one of the largest construction companies in the U.S. The crowning achievement of Warren Bechtel's career was building Boulder Dam in Nevada (later named the Hoover Dam), which provided water for the development of Los Angeles, Phoenix, Palm Springs and the Imperial Valley. As one of the partners in Six Companies, Bechtel would go on to be involved in the construction of many New Deal projects: the Moffat Tunnel in Colorado, the Grand Coulee, Parker, and Bonneville dams, and the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Bridge. By the time Warren's son Steve came on board to head the business, the company was turning its sights away from government projects towards the private sector, particularly oil. And an old schoolmate and early business partner of Steve's from Berkeley, John A. McCone, helped propel the company into the international arena of pipeline development, nuclear power, and nuclear weapons. McCone, "one of the pivotal figures in American policy," (McCartney, Friends in High Places) was chairman of President Dwight Eisenhower's Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and director of the CIA during the John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson administrations. Like many corporations that make money through war-profiteering, the Bechtel and McCone business partnership made much of its fortune by building ships during World War II. Also during the war years, Bechtel undertook the building of the Alaska pipeline, which set the pattern for subsequent controversies in which Bechtel would become embroiled: the government favor of no contract bidding (the pipeline construction was actually conducted in secret by the War Department) and construction mismanagement, including delays and cost overruns. At the direction of the War Department, Bechtel-McCone was also building pipelines and refineries in Mexico, Venezuela, Bahrain, and off the coast of Saudi Arabia. Steve Bechtel and John McCone made over $100 million dollars on less than a $400,000 investment during the war. After the war Steve Bechtel bought out McCone and turned Bechtel Corporation into a service company that avoided debt by dealing with customers who financed their own projects with advance payments: projects that Bechtel not only built but conceived and designed. The biggest of those clients was Standard Oil Company of California, and the place it made its money was Saudi Arabia. From there, Bechtel went to work all over the Middle East, and through its lobbyists essentially became the voice of the Arab world in Washington D.C. Even before John McCone became chairman of the AEC, Bechtel had recognized the potential for profit making in the atomic power industry. In the 1940s Bechtel built several "heavy water" storage plants in Hanford, Washington as part of the Manhattan Project, based in Los Alamos. It was also one of the contractors that built the "Doomsday Town" in the Nevada desert where the AEC detonated a nuclear device to see what would happen to a typical city. It was leveled, of course. Through Steve, Sr.'s connections in Washington D.C and with California utilities that were committed to nuclear energy, it got in on the ground floor of the government's "Atoms for Peace", which proposed transforming the greatest destructive force ever developed into "abundant electrical energy." When John McCone was appointed AEC chairman in 1954, and started moving AEC funding to the private nuclear industry (against the wishes of Harry Truman, who said that nuclear energy was "too important a development to be made the subject of profit-seeking") (McCartney, Friends in High Places), and spreading U.S. nuclear technology overseas, Bechtel was off and running. Greatly expanded during the Nixon administration, the nuclear industry was scheduled to build 31 power plants by 1973, half of which were to be contracted to Bechtel. The first of many boondoggles for which Bechtel was responsible was the nuclear plant in Tarapur, India, where the seed for today's South Asian arms race was planted. The plant experienced major leaks, causing high levels of radioactivity in the Arabian Sea. The Tarapur plant was not the only Bechtel built plant that experienced leaks. According to McCartney, " . . . the entire generation of BWR [boiling-water reactors] plants Bechtel and GE had begun building during the late 1950s were not . . . in compliance with minimum AEC safety requirements." Several Bechtel employees also complained that the company was using "substandard building techniques and faulty welding techniques in the construction of nuclear power plants." Bechtel was accused of trying to silence these complaints and retaliating against the whistle blowers. After a failed attempt to get into the nuclear-fuel enrichment business in the mid-1970s, Bechtel switched its attention to the nuclear clean-up industry. The man who would help lead the company in this next business phase was none other than George Shultz, who epitomizes the government/corporate revolving door routine: first in Washington, as Secretary of Labor and Treasury Secretary under Richard Nixon, then as Bechtel's executive president, and finally, Secretary of State under Ronald Reagan. One of Bechtel's largest and most lucrative assignments is at the Hanford Nuclear Repository, located on the Columbia River in Washington, the largest nuclear waste repository in the country. Hanford stores high-level waste generated from the processing of spent nuclear fuel and has leaked more than one million gallons of nuclear liquid waste into the surrounding environment. Bechtel was awarded the contract to build the waste treatment plant &endash; the Hanford High-Level Nuclear Vitrification Plant &endash; that will take the liquid waste from the leaking underground tanks and turn it into solid glass-waste logs, which will in turn be disposed of in an underground geological repository. At the start of 2005 the plant was estimated to cost approximately $5.8 billion and was supposed to be in operation by a 2011 deadline. Construction on the plant was halted in the summer of 2005 due to flaws in the plans, apparently caused by a fast-tract schedule that began before the design had been finalized. According to a press release from the Government Accountability Project, this "was the result of Bechtel's rush to receive a $15 million bonus for meeting a deadline, coupled with an effective lack of oversight by the DOE." It is now estimated that the plant will cost $11.55 billion (one source says $13.2 billion) and will not begin operation until 2019. Overall, Hanford's cleanup costs are expected to total up to $60 billion and the work to continue until 2035. Bechtel is now gone from Iraq. Its $50 million contract to build the Basra Children's Hospital has been cancelled because the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR) found that the project was almost $90 million over budget and more than a year and a half behind schedule. Bechtel's other contracts expired in October. But the company didn't leave empty handed, by any means. In 2003 and 2004 it was awarded non-competitive contracts totaling $2.85 billion for Iraq reconstruction; the company has thus far been paid $1.95 billion, which has translated into an increase in its overseas revenues of 158 percent in 2004. While Bechtel blames security concerns for its failure to complete the hospital, many point to the fact that Bechtel subcontracted the work to Jordanian and Iraqi companies that resulted in additional overhead, too little managerial oversight, and short-term employment and low pay for the Iraqis. Other contract jobs, particularly to provide electricity, and water and sewage systems, dragged on for years and failed to meet contractual obligations. It took over three and a half years for these systems to exceed prewar levels, but they remain below U.S. government expectations. Three billion dollars has been paid, while only half of the projects planned in these systems have been completed. And of those in operation, according to Bechtel, "not one is being operated properly." The company blames a poor Iraqi work force, but the fact that the U.S. administrator in Iraq fired the upper echelon management work force and hired Bechtel to build systems the Iraqis were unfamiliar with, is more likely where the blame lies. In a July 2006 report to Congress SIGIR stated its intent to investigate all of Bechtel's contracts. No discussion about Bechtel should fail to mention its attempt to privatize the water system in Cochabamba, Bolivia. This topic has been covered extensively and I will only give a brief overview here. When a Bechtel consortium took over the city's water supply from the government, it ignited una guerra del agua during which "peasants from the nearby countryside manned barricades sealing off all roads to the city" to protest what they perceived as the abrogation of their basic human right to clean water. The citizens of Villa San Miguel, a nearby barrio, who had dug their own well and installed a water system to serve its poor community, also joined in the protest when the water consortium took over its water system. The company installed meters to charge fees, which complied with a contract that guaranteed the company a minimum of fifteen percent profit adjusted annually to the consumer price index in the United States. The people of Cochabamba took to the streets over and over again in mass protest and eventually forced the water company officials to flee. The Bolivian government revoked the company's contract but was forced to pay the corporation between $12 and $40 million in compensation. Bechtel is currently involved in other water privatization schemes, including San Francisco, where the company won a $45 million contract to repair and manage the city's water system. "Nuclear laboratories are no longer to be intellectual institutions devoted to science but part of a corporate-business model where research, design, and ultimately the weapons themselves will become products to be marketed. The new dress code will be suits and ties, not lab coats and safety glasses." &endash; Frida Berrigan Bechtel is now one of four contractors partnering in Los Alamos National Security (LANS), a new, site-specific, limited liability corporation that has taken over management of Los Alamos National Laboratory. This is part of a DOE trend to consolidate nuclear weapons businesses in the hands of a small group of corporations, universities, and nonprofits. Damon Hill and Greg Mello of the Los Alamos Study Group take a closer look at what this may mean in their article, "Competition &endash; or Collusion? Privatization and Crony Capitalism in the Nuclear Weapons Complex: Some Questions from New Mexico, May 30, 2006" (http://www.lasg.org/NNSAPrivatization.pdf): "The new LANS contract suggests a new model of conditional long-term, effectively uncompeted, no-bid contracts in which profit incentives and executive compensation will help shape nuclear weapons policy implementation. "As of July 1, 2006 all LANL employees become 'at-will' employees under the LANS contract. While under UC [University of California] management, LANL employees had the right to organize and were provided due process rights to their jobs under California law. Under the LANS contract, this will no longer be the case at LANL. Current Livermore [Nuclear Laboratory in California] employees are already concerned that they will soon face similar changes. "Private corporate management and less government oversight will bring greater whistleblower 'discipline,' tighter control over information and communication, and according to an internal presentation by the incoming LANL director, encouragement of employee reporting of anything or anyone impeding the mission. "Collectively these changes all point to a new ethic in which contract extension and corporate profit could potentially override any and all other considerations. The new LANS/LANL contract awards contractor fees based on performance. When these fees are deadline-driven, as is now the case in plutonium bomb core ('pit') production, nuclear contractors may cut corners, as they have so often in the past, to meet the deadline and make the profit or fee. "These production deadlines are, in LANL's case, possibly the very highest NNSA [National Nuclear Security Administration, part of DOE] priority." One of the most critical considerations that will be at risk is safety. As Joni Arends of Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety points out, "We are concerned that Bechtel will cut corners and risk safety while building the CMRR [the $950 million Chemical and Metallurgy Research Building Replacement at LANL] just as it has at Hanford. The facility itself is enough of a safety risk, and if we couple these problems with a design-as-you-build approach, the impact to our environment and our health will be devastating." NNSA plans to seek further contract consolidation. As we report on page 2 in this issue of La Jicarita News, the agency is currently holding scoping hearings all across the country on its Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) for a program called Complex 2030 &endash; dubbed "Bombplex 2030". While NNSA officially claims the SEIS will "analyze the environmental impacts from the continued transformation of the United States' nuclear weapons complex by implementing NNSA's vision of the complex as it would exist in 2030, as well as alternatives," it essentially is seeking to replace old nuclear weapons with newer, more technologically advanced ones and to consolidate and renovate nuclear weapons facilities that are currently located all over the country. LANL is one of the sites that will be considered. Mello and Hill point out that management and federal oversight are being made subordinate to protecting the new contract and making sure it is profitable. Lack of oversight in the DOE has long been cause for concern in Congress: in a 2006 report, the House Appropriations Committee stated, " . . . The lack of quality federal oversight, which DOE cannot assure, risks producing inaccurate budget estimates that receive only cursory review at critical junctures and are merely passed along to the next authority level." Hill and Mello ask this question: "Why was the House unable to reform DOE and especially weapons complex contracting practices. . . ? No set of answers on this subject would be complete . . . without considering the very particular role of the Senate Energy and Water Appropriations Committee, whose chairman Pete Domenici has made funding for the two nuclear weapons laboratories in New Mexico and the nuclear industry they anchor a central aspect of his career &endash; or perhaps its centerpiece." Will the fact that our other senator, Jeff Bingaman, is now the head of the Energy and Water Appropriations Committee, insure better oversight of the Lab? Not unless we continue to demand it. Contact the organizations in New Mexico working to expose and abolish these laboratories of mass destruction to see how you can help: Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety (CCNS), www.nuclearactive.org; Los Alamos Study Group, www.lasg.org; and Nuclear Watch New Mexico, www.nukewatch.org. Editorial: Politics as Usual in Rio Arriba CountyBy Kay MatthewsTo no one's surprise, politics as usual played out at the November 30 Rio Arriba County commission meeting on the controversial cell phone tower in Chimayó. The dance around "the right thing to do" wasn't even evinced with dexterity or savoir faire: it was displayed as the defensive posture of a group of men afraid of being sued by T-Mobile. As we've previously reported in La Jicarita News, the Chimayó Council on Wireless Technology (CCWT) organized to protest the placing of a cell phone tower by T-Mobile near the historic Plaza del Cerro and Santuario in the heart of Chimayó. Rio Arriba County Planning director Patricio Garcia administratively approved the tower in January of 2006, based on an outdated 1996 ordinance, which had been replaced by a 2000-01 ordinance that requires all proposed towers obtain a permit for a zoning change, provide for public notification, and be reviewed by both the Planning and Zoning Committee and the Board of County Commissioners. None of this happened, and when the CCWT looked at the T-Mobile file at the county, members also discovered that the phone company had failed to file a proper application or pay the application fee. The group proceeded to file a complaint, and after receiving no official response from the county, filed an appeal of Garcia's decision on August 15. The only response the county could muster against the overwhelming evidence that the tower is illegal and the county is responsible for its lack of oversight, was procedural: the commission would only address the issue of whether the CCWT's appeal was filed within a 15-day appeal period (there is no language in the 2000-01 ordinance that even states the terms or time limits of an appeal) and that the allegations that the tower is illegal were not presented by an attorney. Congratulations, commissioners, you've completely bought into the dominant culture's modus operandi: only lawyers can tell us what "is the right thing to do." You made a pretty pathetic display of how money talks&emdash;fear of a lawsuit from T-Mobile if you so much as ask the company to resubmit an application and go through the correct approval process&emdash;and community accountability walks&emdash;out the chamber door. CCWT intends to take this issue to district court. All of those who have committed their time and energy&emdash;uncompensated, of course&emdash;to hold their elected officials accountable shouldn't have resort to this. But according to former Rio Arriba County Assistant Zoning director Gilbert Chavez, "District Court would not rule favorably on a case in which an entity has not adhered to their adopted ordinances, policies and procedures . . ."

|

Home | Current Issue | Subscribe | About Us | Environmental Justice | Links | Archive | Index

Copyright 1996-2002 La Jicarita Box 6 El Valle Route, Chamisal, New Mexico 87521.