|

|

|

Volume XII |

April 2007 |

Number IV |

|

|

Abiquiu: Divisiveness & Discord By Mark SchillerHundreds Protest Santa Fe County's Application to Transfer Water to Supplemental Wells By Kay Matthews |

Editorial: Down the Legislative Black Hole By Kay Matthews Editorial: It's All One Big Water Grab By Kay Matthews |

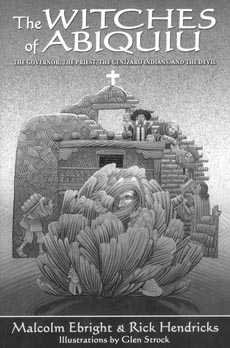

Abiquiu: Divisiveness & DiscordBy Mark SchillerThe community of Abiquiu has a unique and incredibly rich history. It's believed that the area was first settled in the eleventh and twelfth centuries by Native Americans fleeing the droughts that afflicted Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon. Spanish colonists from the Española Valley began using the area along the Chama River for grazing in the seventeenth century. And although the Spanish colonial government made a number of land grants in the area during the first half of the eighteenth century, they were constantly being abandoned because of the incessant raids made by nomadic tribes. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, Spanish Governor Tomás Vélez Cachupin believed it was crucial to secure the northern boundary of Nuevo Mexico and in 1754 he made an historic decision: he granted a "pueblo league" (approximately 17,000 acres) to thirty-four Genizaro families at Santo Tomás Apostle de Abiquiu. Interestingly, the new settlement stood atop the ruins of a prehistoric pueblo. Genizaro is a generic term the Spanish applied to people of Native American descent formerly held in servitude by the Spanish who, more or less, adopted the colonists' language and way of life. According to historian Malcolm Ebright, who has written extensively about Abiquiu, "Vélez Cachupin realized that the old system of making land grants primarily to elite members of society was not conducive to frontier defense. The elites could not always be relied on to defend their land to the death. Genizaros were the best Indian fighters because they knew the enemy. They knew the Comanches and the Utes' strategies and tactics, because among them were members of these Indian tribes." In fact, the Genizaros of Abiquiu, who were of mixed descent including Hopi, Plains Indians, and Pueblo, were part of a growing population of landless poor that Vélez Cachupin shrewdly enlisted to settle frontier communities and act as a buffer for the established villas of Santa Cruz de la Cañada (Española), Santa Fe and Albuquerque. Although the Genizaros of Abiquiu were ostensibly Hispanicized and Christianized, the Spanish colonists inflicted witch-hunts, trials, and exorcisms on the people of the Pueblo during the 1760s because of their continuing attachment to their indigenous cultures (see Ebright's book The Witches of Abiquiu for a detailed account of this fascinating period). And, while they were considered an Indian pueblo by the Spanish and Mexican governments, many residents feel they were robbed of a portion of their heritage by being adjudicated by the United States government as an Hispanic community grant rather than a Native American pueblo grant. Ironically, the grant's patent reads, "To the half-breed Indians of Abiquiu." Abiquiu's history has also been significantly impacted by the legacy of artist Georgia O'Keeffe, who took up residence there in the late 1940s and remained until her death in 1986. O'Keeffe's well known and highly commercialized art of this period focused on Abiquiu's spectacular landscape. Her subsequent "canonization" by art brokers has made Abiquiu a haven for O'Keeffe groupies and "New Age" entrepreneurs. To paraphrase movie star and Abiquiu landowner Shirley MacLaine, "The high desert was calling me." So now the Abiquiu landscape is dotted with high-end, custom built, passive solar adobes and land prices, as you can imagine, have sky-rocketed way beyond the means of the families whose ancestors originally settled the area. (Local rancher and community activist Virgil Trujillo told La Jicarita that new development has pushed land prices so high that locals soon won't be able to pay their property taxes, much less buy land.) There's also a steady flow of tourists making the pilgrimage to "O'Keeffe Country," as the Abiquiu area has become known. As a result, the community is factionalized: many locals are offended by newcomers' ignorance of and insensitivity to local history, custom, and tradition. More importantly, they're outraged by newcomers' attempts to exploit their heritage and their homeland. The friction between these two factions was in stark evidence at the April 4 Rio Arriba County Planning and Zoning meeting in Española. Five of the six projects the commission was considering for approval were in or around Abiquiu, and the hearing room was filled to overflowing with community members there to express their support or disapproval of one or more of the proposals. What became clear from the outset was that all factions within the community accepted the fact that the area is going to be further developed. The debate, therefore, focused on what that development would consist of and who would be the beneficiaries. Two of the proposals before the commission are emblematic of the larger issues facing the community. These are: 1) a proposal by Texas oil heiress Helen LaKelly Hunt and associates to create "Bievenidos," a community cultural center on an approximately twelve-acre property near the Abiquiu Post Office; and 2) a proposal by Seledon and Alice Garcia to build a lodge and restaurant on a thirteen and a half-acre property just outside Abiquiu. Helen Hunt is the second youngest of Texas oil tycoon H.L. Hunt's 14 children. Her website states that, among other things, "She is founder and president of The Sister Fund, a private women's fund dedicated to the social, political, economic, and spiritual empowerment of women and girls." According to Abiquiu resident and community activist Sabra Moore, however, Hunt has had a troubled history with the community since she bought an historic ranch nearby in the mid- 90s. In an e-mail Moore sent Rio Arriba County Assistant Planning Director Gabriel Boyle she said, "Ms. Hunt has sponsored several projects in the area on previous occasions, including her earlier support for the library, attempts to develop micaceous pottery, a cattle operation and other endeavors. Her involvement has often been capricious, ending abruptly and affecting the viability of the projects when she suddenly withdraws support. The micaceous pottery studio is an example that parallels the proposal for a community center. Rather than offering support to existing potters, she established a pottery studio based on a work-for-hire system in which the potters were simply paid slightly above the minimum wage to create their ceramics. The pottery was then sold at a substantially higher profit that did not benefit or empower the potters themselves. An individual cannot create a community center; that needs to be developed from a strong community base." With regard to both the cattle operation (which folded after five years) and the pottery studio, Moore, in a telephone conversation with La Jicarita, questioned whether Hunt's motives were entirely philanthropic since she micromanaged both organizations and asserted her right to a "return" on her investment. El Pueblo de Abiquiu Library and Cultural Center Director Isabel Trujillo also questions Hunt's motives and methods. Trujillo told La Jicarita that Hunt formerly gave the library and cultural center substantial financial support while her non-profit group, Luciente, managed the money and oversaw the programs. She believes that Hunt withdrew her support when local people began to assert themselves. She feels that if Hunt's intentions were truly philanthropic, like O'Keeffe, who anonymously provided funds for many community projects and underwrote the cost of college educations forseveral community members, she would have ensured the projects she supported were community driven. Instead, Trujillo believes, Hunt is now trying to undercut the library and cultural center's successful programs by duplicating many of its services. Trujillo says that when Hunt withdrew her support of the library, she took the umbrella organization that served as the library's non-profit fiscal sponsor with her, making it difficult for the library to obtain funding. Hunt's organization then applied for its own funding to create an after-school program for area children when the library and cultural center already had a free after-school program that tutored children in their school subjects and taught local history as well. Trujillo points to a newly initiated program that trains community youth to conduct historical tours of the area as another program at risk. She told La Jicarita that many visitors come to Abiquiu to tour the Georgia O'Keeffe house but are unable to do so because there is usually a two-month waiting list. These tourists often wander through the village and land grant, unaware that these are culturally sensitive areas. In response, the library and cultural center enlisted the help of retired teacher and historian David Lopez to train local students to conduct historical tours. These tours not only convey the indigenous peoples' perspective but also channel some of the enormous revenue being generated by the O'Keeffe connection back into community programs rather than into the pockets of tourist entrepreneurs. If Hunt builds her cultural center, Trujillo fears that there will be competition for this money as well. Moreover, she believes that the majority of the community is unaware of Hunt's plan and its potential effects. She points to the fact that Hunt's organization has held no public meetings to discuss their master plan and solicit public input. She's concerned that the property Hunt has proposed for the project includes an easement into the grant's common lands and that no traffic study has been conducted for the area, which is already congested and dangerous. She also says she finds promotional literature for the new cultural center that asserts that Abiquiu is not a federally recognized Pueblo disrespectful and offensive. In spite of all this, she says she remains hopeful that the two groups can find a way to work together to create a comprehensive plan that serves the best interests of the community at large without duplicating programs and services. Unfortunately, rather than postponing a decision on Hunt's proposal in order to give community members additional time to find a compromise solution, the Planning and Zoning Commission voted unanimously to approve Hunt's master plan. That plan will now undergo final consideration by the County Commission at its April 26 meeting in Tierra Amarilla. Seledon and Alice Garcia's proposal to build a lodge and restaurant in an area adjoining Abiquiu also highlights the divisiveness plaguing the community. The Garcia family has been in the community for generations and they are members of the land grant. According to testimony before the commission, they own a contracting company that's one of the few businesses that provides employment opportunities within the community. The business plan for the Garcias' new proposal calls for the creation of between thirty and forty additional jobs. Ten community members spoke in support of the Garcias' proposal, emphasizing the importance of local jobs for a community in which many members must commute to Española, Los Alamos, and Santa Fe to find work. They also cited the Garcias' long history of supporting community programs such as the library. One community member was outspoken in his denunciation of outsiders who've come into the community with their enormous wealth, built garish mansions, and now want to prevent local community members from benefiting from the influx of tourists because they don't want commercial development in their backyard. Four people spoke in opposition to the Garcias' proposal, three of whom were members of a family whose land is immediately adjacent to the proposed lodge and restaurant. They expressed concern that the project would use more water than the proposed plan states, cause traffic problems that could be exacerbated by the potential for the restaurant to serve alcoholic beverages, and affect the night sky with its parking lot lighting. The Garcias responded with a letter from the Office of the State Engineer affirming that the lodge and restaurant's water use would not affect the water table. They also told the commission that they were not, at this time, considering acquiring a liquor or beer and wine license and that they would take steps to minimalize the effect their parking lot lights had on neighboring properties. Apparently a rumor had circulated within the Anglo community suggesting that the land grant wants to regain Pueblo status in order to build a casino and the Garcias' proposal was a first step towards achieving that goal. This also increased polarization and opposition to the proposal. Trujillo insists, however, that nothing could be further from the truth. She points to the fact that the Garcias intend to name the lodge and restaurant "El Genizaro" out of respect for Abiquiu's heritage and says this rumor highlights the distrust that's fueling many of the community's problems. In a split vote the Planning and Zoning Commission also approved the Garcias' proposal. Although all of us who live in the rural communities of el norte are dealing with issues of gentrification and commercialization, Abiquiu is clearly at the forefront of that battle. The Genizaros of Abiquiu have survived slavery, witchcraft, injustice, and poverty. It remains to be seen whether they can find a way to remain economically viable while maintaining their culture and traditions. Hundreds Protest Santa Fe County's Application to Transfer Water to Supplemental WellsBy Kay MatthewsIn March Santa Fe County filed eight applications to transfer 110.22 acre feet (afy) of in-basin water rights to 19 wells throughout the county. The move-to wells are spread out from South 14, through the community college area and Agua Fria Village, to NM 599 near the intersection of CR 62. According to the county, it needs these wells, which will supplement the Buckman wells and future surface water diversions (the Buckman Direct Diversion) from the Rio Grande, to serve utility customers in the growing areas south and west of Santa Fe. The proposed transfer rights belong to developers who are required to provide water to the county utility before getting approval for their building projects. But the fact that the public doesn't know which of the 19 wells will actually be pumped or how much water will be pumped at each well has many Santa Fe County well owners up in arms about the proposed transfers. The county says those decisions will be made after the Office of the State Engineer (OSE) rules on the applications, with public input and review by the County Commission. Some of the proposed move-to wells aren't owned by the county, or are located in the controversial subdevelopments of Suerte del Sur (where Gerald Peters previously tried to put in a well but eventually hooked up to the county water system) and Rancho Viejo, and even several of the county commissioners seem to think the water division has the cart before the horse. Commissioner Jack Sullivan was quoted in The New Mexican saying that the Commission needs to give direction on where it wants to see new wells (he also went on record opposing the use of the Rancho Viejo well, one of the 19 sites, because it will bring more development into his district). The Santa Fe Well Owners Association, working in conjunction with other community groups and under the umbrella of the Santa Fe Basin Water Association (SFBWA), set up a web site encouraging county well owners to protest the transfer applications. In 2003 the SFBWA protested the city's plan to drill four supplemental Buckman wells on county land to access 4,000 afy of water that it had been unable to pump at the existing nine Buckman wells. SFBWA argued that these new wells, in the La Tierra area near the original wells, could impair existing private wells. The protest is currently in settlement negotiations. SFBWA was formed in the 1970s as the Agua Fria Water Association to watchdog all water transfer application in the Santa Fe area to make sure they didn't impact existing water rights. The philosophy behind the group is that the city and county need to take care of existing water users and make sure that water management agencies act as stewards of our water resources. The OSE received hundreds of protests regarding the 19 supplemental wells, which will be forwarded to the litigation unit over the next few weeks. The hearing officer (yet to be appointed) will have to determine how the protests are handled administratively. According to David Gold, president of the Santa Fe Well Owners Association, the commissioners and the water division are both at fault for fast tracking these applications before completing the promised water modeling that would address whether these supplemental wells will be sustainable, will impair other wells, and are economically viable. He also points out that there doesn't seem to be a plan for how the county will deal with potential dry wells, what the infrastructure plans are associated with the new wells, and what future water uses will be associated with the wells. His main concern is that these wells may potentially contribute to the depletion of the aquifer and long-term environmental consequences. Why, then, is the county in such a hurry to get these supplemental well transfers in place? According to Mary Young of the Water Rights Division of the OSE, her office originally had discussions with the folks in the county water division last year about the priority dates associated with the potential transfers-whether they were pre-Rio Grande Compact rights and if that would affect the applications-but in May communicated to division head Stephen Wust and hydrologist Karen Torres that there weren't any OSE policy changes that would affect the proposed transfers. La Jicarita News asked Young how her department will handle all these applications without knowing which move-to wells will actually be used by the county. She said the OSE would have to look at each of the wells regardless of whether it will eventually be used. "This is to the detriment of the county and will mean more work for us." La Jicarita News was unable to contact water division head Stephen Wust and was referred by hydrologist Karen Torres to the county public affairs officer, Stephen Ulibarri. He emphasized that the county wanted to move forward to meet the needs of its residents with a conjunctive water stategy (surface and ground) and was unconcerned that the OSE would have to review all 19 potential move-to wells regardless of whether they are eventually used. He also framed the issue as one that involves pro-growth and anti-growth proponents, and that no matter how the county proceeds, some folks will never be happy about it.

|

A coalition of community groups sent an amended 60-Day Notice of Intent to Sue the Department of Energy and Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in April (see La Jicarita, June 2006). The letter charges LANL with an unprecedented number of violations of the Clean Water Act (filing a Notice of Intent to Sue is required under the Clean Water Act prior to filing a lawsuit in court): •Failure to conduct adequate, representative monitoring • Failure to report violations • Failure to have pollution control measures in place • Failure to comply with water quality standards • Unauthorized discharges The groups charge that New Mexico's water supply is threatened by highly toxic pollutants, including PCBs at more than 25,000 times the New Mexico Water Quality Standard. Other toxins include 1,4-dioxane, hexavalent chromium, nitrates, fluoride, perchlorate, high explosives, selenium, and numerous radioactive elements. Six of the groups had previously filed a Notice of Intent to Sue in May of 2006, but are now refiling, along with three new groups and two individuals, because of new corporate management of LANL (Bechtel, BWT Technologies and Washington Group International, and the original LANL manager, the University of California). The list of groups and individuals includes: The coalition is represented by Matthew Bishop of the Western Environmental Law Center. For further information contact Sadaf Cameron and Joni Arends, Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety, 505 986-1973 or 913-0040; or Michael Jensen, Amigos Bravos, 505 362-1063.

CONSERVATION RAFFLE A $100 ticket buys you a chance to win one of these fantastic vacations, while supporting land conservation in the Taos area. ONLY 250 TICKETS WILL BE SOLD! DRAWING MAY 11, 2007 GRAND PRIZE: One week at the Casas de Santa Cruz in Yelapa, Mexico (airfare for two included, but lodging for up to five people) FOUR OTHER PRIZES AS WELL More information, trip details, and web links at www.taoslandtrust.org. Editorial: Down the Legislative Black HoleBy Kay MatthewsDespite what the cheerleaders are saying (and we all know who the head cheerleader is), the 2007 New Mexico legislative session was as frustrating, disappointing, and ridiculous as ever. Without going into the macho machinations over the extended session, let's take a look at the few significant bills that passed and the many bills that disappeared down the black hole of the regular session. Bills to approve the use of medical marijuana and to prohibit cockfighting are all well and good (when will this country legalize marijuana, period?), but we have to remember why they passed this session, after failing for many, many years: Bill Richardson pushed for their passage because of his presidential bid. The bill to abolish the death penalty, a critical bill that has been introduced during many sessions, failed to pass, however, largely because of Richardson's equivocation. It remains controversial nationally and I suppose he and his team of strategists couldn't figure out if his support of its abolition would hurt or help him in his bid. Only one person has been executed in New Mexico in 47 years; however, others remain on death row subject to this barbaric practice of state killing while New Mexico spends millions of dollars during lengthy appeals processes. The domestic partnership bill failed to pass the regular session despite Richardson's support (another issue whose time has come nationally). The bill would provide all the rights and responsibilities of married partners to unwed partners, gay or straight. Republicans and conservative Democrats joined together to emasculate the language in this bill, and eventually doomed its passage. Particularly disappointing was Senator Carlos Cisneros' (D-Taos) opposition. He promotes himself as a progressive democrat, particularly with regard to equity in water issues, and his opposition to this bill, along with his vote with Republicans to kill the impeachment memorial (see next paragraph) will be remembered by his constituents. The Senate refused to hear it in the extended session. While the conservatives tried to demean the importance of the impeachment memorial by whining that legislators should keep their minds on more local, "meaningful" legislation (such as Representative Youngberg's memorial, "Recognizing that the ancient Macedonians were Hellenes and that the inhabitants of Macedonia today are Hellenic and part of the northern descendents of Greece, Macedonia"), hundreds of constituents thought the memorial meaningful enough to consistently pack committee hearings and write hundreds of e-mails and letters to their representatives in support of the memorial. Which, by the way, if approved by the state legislature of New Mexico, would have required that Congress begin hearings to consider impeachment in Washington. Afraid to actually hear the bill on the floor of the Senate, nine Democrats joined with Republicans to prevent its debate. Another important memorial that failed opposed the Washington-passed Real ID Act. It stipulated that no state funds be appropriated for its implementation and urged Congress to repeal it. This unfunded federal mandate requires that people obtain a new identification card in order to enter airports or federal buildings, open a bank account, or obtain a driver's license. It would cost the state approximately $37 million to implement and would violate our civil liberties, particularly those of immigrants and the elderly, who often lack birth certificates. In this so-called "year of water" very little legislation of import was actually passed, and projects that did pass were woefully underfunded. But as Trudy Healy, Arroyo Hondo activist and member of the Water Trust Board, points out, this year it was not so important what passed but what didn't pass. There was an attempt by the governor's office to subvert the good work of the Water Trust Board, the appointed agency that is responsible for reviewing and recommending funding for potential water projects around the state and for helping implement regional water plans. The governor's office attempted to shove a bill (HB 781), described by those in the know as a "plumbing" bill, through the session without committee hearings. The bill would have created a new bureaucracy called the Office of Water Infrastructure Development to oversee the Water Trust Board and would have essentially placed millions of dollars in water funding in the hands of urban/suburban bureaucrats. According to the folks who represent rural areas and have lobbied long and hard to make sure the Water Trust Board funds watershed restoration projects as well as infrastructure projects, this bill would have undermined grassroots, bottom-up control of water in favor of top-down, urban development. Once they got wind of its secret passage through the session they raised a stink and the bill was tabled. Richardson initially requested that it be brought back to life in the special session, but ultimately it didn't make his list. Which brings us to the final debacle, the attack by Monsanto Corporation on the memorial recognizing the significance of indigenous agricultural practice and native seeds. This memorial endorsed the collaboration between the Native American and Hispano communities traditional agricultural practices and the idea of seed sovereignty, threatened by genetic engineering and corporate patenting of genetic material. Monsanto showed up in full force to lobby legislators from the southern part of the state, where there is significant support of genetic engineering of seeds by the state department of agriculture and NMSU. Monsanto wanted any language that warned against corporate control and manipulation through genetic engineering and seed patening stricken from the language of the memorial, and, as wealthy lobbyists usually do, it got its way. The legislative session wastes the time and energy of so many people in endless committee hearings, backroom finagling, floor fights, and power lunches. Otherwise rational people, who work for organizations that are involved in advocacy and community organizing, seem to accept the premise that the policy work of the legislature trumps all other efforts, and for one or two months a year let important issues fall by the wayside while they pursue one or two bills that might or might not be implemented. Is there a solution? One seems obvious to me. The legislature should be reduced to one chamber with members elected as paid reprensentatives, and the number of bills introduced in a single session must be severely limited. Those bills must be drafted by coalitions of individuals and groups who can come to a consensus before the session begins. Lobbyists should be severely restricted (they should probably be eliminated altogether) in how they operate within the confines of the session (no power lunches or two martini dinners). A much shorter session could then be held, allowing regular citizens to run for office rather than the rich lawyers and business people who now dominate the legislature. Public funding of legislative races is absolutely essential. The legislators wasted precious time this session trying-unsuccessfully-to pass an ethics reform package that continued to skirt the issue that until there is public financing of all candidates, not just the proposed judicial candidates, there will continue to be payback and corruption that tarnishes the entire legislative body. Unfortunately, none of this will likely happen, and we'll continue to fall down the black hole in ever increasing numbers. Editorial: It's All One Big Water GrabBy Kay MatthewsThe chickens are coming home to roost, so to speak, as the state, after 50 years of indiscriminate pumping of the aquifer to facilitate urban growth, now impacting surface water flows, scrambles to find the water to settle Indian water rights claims and meet its compact obligations to Texas. Albuquerque, after years of assurances that its underground "lake" would supply the city for years to come, is now building a direct diversion from the Rio Grande. Rumors on blogs and not-for-public e-mails are circulating through cyberspace regarding the machinations of water brokers, both private and public, trying to find water for the city and county of Santa Fe. And all of them are looking at agricultural water rights, in the middle Rio Grande basin and el norte, to solve their problems.

As part of the research for the article on page 4, I spoke with Tom Simons, an attorney and parciante who is representing the Acequia de la Cienega in several transfer protests, including the applications to the county supplemental wells. The traditional community of La Cienega is under siege, sitting at the lower end of the Santa Fe County system, and Simons has filed numerous protests over the years to protect the village's springs, including the transfer application for the Hagerman well (near the horse park in Cieneguia), which the county wants to use as a high-production well. The village also has had to deal with the next-door development Santa Fe Ranch (in which former mayoral candidate David Shutz has an interest) trying to acquire water rights after the county refused to service the development through its utility. Simons is skeptical of the county's position that it will rely on the Buckman Direct Diversion project for its main source of water and use the 19 supplemental wells as insurance for drought. He's also seen an enormous increase in the number of transfer applications in the past six months by both the city and county. Recently, many of these proposed transfers, both ground and surface water rights, are from the middle Rio Grande basin to the Buckman Well Field and the Buckman Direct Diversion. For example, in The New Mexican's March 27 legals, the city of Santa Fe applied to transfer 6 afy of surface water from the Los Padillas Acequia in the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District in Albuquerque's South Valley. The water rights are owned by Wiv Co. on land owned by Jonathan and Donna Galvez. The transferred water will be used to offset depletions on the Rio Grande stemming from pumping at the 13 Buckman wells. What do all these transfers mean? Many of them are offsets by the city and county for the direct diversion they will be making from the Rio Grande once a dam is built, although it's unclear why they're being transferred to a diversion that won't be built until at least 2010 instead of to the Buckman wells. Some of them, however, may be slated for the Aamodt settlement. There's a proposal circulating, written by Santa Fe County attorney John Utton, for an exchange of water rights below Otowi Gauge at the Buckman Direct Diversion for San Juan/Chama water above the gauge at San Ildefonso Pueblo. Remember, the Office of the State Engineer hasn't approved transfers from the northern basin, above Otowi Gauge, to the middle or lower basins below the gauge, because of the Rio Grande Compact, which determines the state's delivery obligations to Texas. A change in the point of diversion from one side of the gauge to another would affect the quantity of deliverable water. To get the water for the Aamodt delivery system in the Pojoaque basin, the pueblos could tap into the water rights market in the middle Rio Grande, transfer them to the Buckman Direct Diversion and use them above the gauge. A like amount of San Juan/Chama water, owned by the city and county, would be exchanged for diversion above the gauge at San Ildefonso. Santa Fe County seems to be right in the middle of all the wheeling and dealing. It' s responsible for finding water rights for the water delivery system in the Pojoaque basin as part of the Aamodt adjudication, and it seems unable to develop a sustainable water plan that ties growth to existing water supplies. In previous articles, I've pointed out that many non-pueblo residents in the Pojoaque basin don't want a water delivery system and want to see the county get out of its position as water broker. But the powers that be seem hell bent on playing high stakes in the water market game, along with big-time developers with names like Gerald Peters and Richard Cook of Española, and we're going to see more and more water rights-paper rights, of course, increasingly vulnerable as our drought continues-transferred to Santa Fe and Albuquerque.

|