|

|

|

Volume VIII |

March 2003 |

Number III |

|

|

Sangre de Cristo Land Grant Activists Tell Their Story at the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Conmemoria at the Oñate Center By Kay MatthewsState Legislature Considers Strengthening Acequia Autonomy By Mark Schiller Book Review: This Sovereign Land: A New Vision for Governing the West By Daniel Kemmis Reviewed by Kay Matthews |

Keynote Speaker at the New Mexico Farming & Gardening Expo Talks Revolution By Kay Matthews |

Sangre de Cristo Land Grant Activists Tell Their Story at the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Conmemoria at the Oñate CenterBy Kay Matthews"What we are seeing today is the continuation of Manifest Destiny." That's how Shirley Romero Otero described what she and the community of San Luis have been up against in their 21-year struggle to regain access rights to the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, the vast upland of the Culebra Valley they call "La Sierra" (see La Jicarita, August 2002). Otero was part of a panel of land grant activists who appeared at the February 2 conmemoria of the Treaty of Guada-lupe Hidalgo at the Oñate Center. Their victory, handed down by the Colorado Supreme Court on June 24, 2002, granted the landowners, who are the successors in title to the original settlers of the private Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, access and use rights to grazing, firewood gathering, and timber harvesting on their former grant lands now owned by Lou Pai, a former Enron executive. Malcolm Ebright, panel moderator and historian currently establishing a land grant data base at the Oñate Center in conjunction with the Center for Land Grant Studies, and Jeff Goldstein, lawyer for the land grant plaintiffs, cite the Colorado decision as particularly significant. It begins to reconcile Spanish and Mexican law with American law by looking at the historical context, in this case, the Beaubien Document, which originally granted the settlers access right to the common lands of the grant. This precedent may help validate the community land grants in northern New Mexico that look to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo as they seek restitution. Goldstein, who had just presented a paper on the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant decision before a law conference in Washington D.C., also believes the decision will bolster other indigenous land claims around the world.

Attorney Jeff Goldstein A representative of Tom Udall's northern New Mexico office, Thomas Garcia, cautioned the audience that the soon to be published General Accounting Office (GAO) study of community land grants will not be a "vindication" of the abrogation of those grants but will offer possible remedies that could be implemented through congressional legislation. Udall, he said, is helping keep alive the bill that would establish a presidential commission, housed at the Oñate Center, to explore remedies and maintain a data base. There remain several legal hurdles for the Sangre de Cristo heirs. The court has yet to rule on whether the access rights should be extended to all those who can trace land ownership within the grant, which includes families of the traditional villages of the Culebra River drainage and could number about 1,000 people (a previous court ruling had limited the names to seven landowners identified by previous owner Jack Taylor in the abstract title to his land). While Goldstein acknowledges that the Colorado Supreme Court decision will no doubt be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, it is highly unlikely it will be heard. Also, the final order of access probably won't be issued for at least a year, which is unfortunate, as the people of the valley are coping with the effects of drought and will be denied access to the higher pastures for grazing for another season. The current owner of the grant, Lou Pai, has blocked off all access, and community members have had no communication with him regarding future management plans. Pai acquired the grant in two separate transactions: as La Jaroso Ranch L.L.C. in 1997 and Beaver Dam Ranch L.L.C. in 1998. Another company was formed to purchase land in surrounding villages. Because of his background as an expert in oil and gas leases with Enron, and the fact that his legal team are oil and gas attorneys, heirs worry that his "gated mountain" will become the focus of oil and gas leasing.

Maria Mondragon Valdez and husband Arnold Valdez, a land grant plaintiff In her panel presentation, activist Maria Mondragon Valdez acknowledged that there are many conflicting visions for La Sierra, above and beyond what Pai may have in mind. The Land Rights Council, the people who first organized in the 1970s to regain their grant rights, have a vision of communally shared rights. They have planners, including Maria's husband Arnold, who are ready to start work on a land use plan for the area. There are those who look to the land for commercial enterprise or private profit. There are those who have an outside vision of ecotourism or academic research. And there are those who believe the access rights go with the land, not with those who can prove they are heirs to the original settlers. But both Valdez and Otero believe that the long, hard work of all the people of the valley - from the viejitos who searched their houses for legal and historical documents, to the Chicano activists of the 70s who took up the struggle, to the Joe Lovato's and Ray Otero's and Charlie Jaquez's who have made this fight their life's work - will have not been in vain.  Raymond Maestas, land grant plaintiff ANNOUNCEMENTS• La Jicarita Valley Wastewater Committee (LJVWWC), working since 1996 to protect water quality in the Jicarita Valley, will soon begin a door to door survey of residents of the Peñasco area communities. This survey is part of a larger campaign to gather data that will allow the LJVWWC to apply for funding to construct wastewater facilities throughout these Jicarita Valley communities of Picuris Pueblo, Rio Lucio, Chamisal, Peñasco, Rodarte, Llano San Juan, Vadito, Llano de Llegua, Llano Largo, Sipapu, Las Mochas, Placitas, Upper and Lower Ojitos and Tres Ritos. Also, leading up to the official survey "kickoff", the LJVWWC will host an Information Fair at the Peñasco Community Center. The date for the Information Fair/Survey Kickoff is tentatively scheduled for March 22, 2003. Final confirmation of the date will be posted, no later than March 7, 2003, at the Peñasco Post Office. Attendance at the fair will include some of the entities that the LJVWWC has been working with, including: state and federal government funding and regulatory agencies, state, county and local politicians, private sector non-profit corporations, Taos County Agencies, etc. The fair is being presented to provide a venue for discussion, distribution of informational materials, education and question and answers regarding the work of the LJVWWC and its partners. LJVWWC encourages all community members to attend the fair; food & soft drinks will be provided. LJVWWC is still recruiting hard-working, self-motivated individuals who care about their community to assist with a door-to-door informational campaign. Details are as follows: Position: Community Liaison Salary: $10.00/survey completed (45 minutes to an hour) Job Description: Attendance at an orientation and training session sponsored by Border WaterWorks, Picuris Pueblo and the La Jicarita Valley Association of Mutual Domestics, organized to teach successful applicants public relations skills and to teach basics about water and wastewater systems and the relationship between these systems and water quality. Attendance at relevant community meetings during the project to educate the residents of the Jicarita Valley about the information campaign and how the information will be used to reduce the public health risks in the valley. Acting as a liaison between the entities listed above and the residents of the Jicarita Valley as needed to obtain completed door-to-door surveys. If after reading the above job description you are interested in participating, please contact: Julia Geffroy; Picuris Pueblo Representative; 587-0110; Pete Pacheco; Peñasco Representative; 587-0410; Clyde Gurule; Rio Lucio Representative; 587-2538; George Maestas; Rodarte Representative; 587-2560; Roger Martinez; Llano San Juan Representative; 587-2864; Ronald Rodriguez; Chamisal Representative; 587-0188; James Coleman; Sipapu Representative; 587-2240 State Legislature Considers Strengthening Acequia AutonomyBy Mark SchillerMany members of the acequia community are hoping that two pieces of legislation currently being considered by both houses of the state legislature become state law. Senate Bills 123 and 124 sponsored by State Senator Carlos Cisneros and House Bills 302 and 303 sponsored by State Representative Ben Lujan have made it out of committee and could give acequias the authority to better protect themselves against loss of water rights due to transfers and forfeiture. Senate Bill 123 and House Bill 303 both propose to amend state regulations governing changes in point of diversion or place and purpose of use. The amendment to Chapter 72, Article 5 NMSA 1978 states: "An acequia or community ditch may require that a change in point of diversion or place or purpose of use of a water right served by the acequia or community ditch, or a change in a water right so that it is moved out of or into and then served by the acequia or community ditch, shall be subject to approval by the commissioners of the acequia or community ditch or as otherwise provided in the bylaws, rules or regulations of the acequia or community ditch. The change may be denied if it would be detrimental to the acequia or community ditch or its members." In layman's terms this means that if an acequia adopts this provision into its bylaws, all proposed transfers of water rights out of that acequia system would be subject to the approval of the commission. The amendment further stipulates that the state engineer must abide by the decision of the acequia commission. However, under pressure from the Office of the State Engineer (OSE), the original bill has been modified to also stipulate that the commission must make a decision in writing within 120 days on an application for transfer of water rights out of the acequia. This letter of decision must specify the commission's reasons for believing the transfer will be detrimental to the acequia. In the event that the applicant is not satisfied with the commission's decision, he or she has 30 days to appeal the decision in district court. "The court may set aside, reverse or remand the decision [of the acequia commission] if it determines that the commissioners acted fraudulently, arbitrarily or capriciously or that they did not act in accordance with law." This modification essentially relieves the OSE of the obligation and financial responsibility of undertaking a transfer protest hearing and makes the appeals process the responsibility of the state district courts. Additionally, the original bill has been modified to exclude "water rights or lands owned by or reserved for an Indian pueblo." Acequias, which are dependent on the cooperation of all parciantes to provide the hydrological surge, manpower and financing necessary for the operation and maintenance of their irrigation systems, are endangered by transfers of water rights which can jeopardize all of these resources. Moreover, this legislation implicitly supports the belief held by many parciantes that acequias are a communally owned resource which individual parciantes do not have the right to impair. The current state adjudication process, by contrast, maintains that a water right is an individual private property right which each water right owner has the authority to sell on the open market. While most parciantes feel that a water right is inextricably tied to the land and community with which it is associated, there are some parciantes who claim that this legislation is an assault on their right of private ownership. Developers, in and around municipalities who must demonstrate they own the necessary water rights to facilitate development and therefore seek to buy water rights wherever they are available, may also raise objections to this legislation. The second piece of legislation would establish an acequia's right to create a community water bank. Senate Bill 124 and House Bill 302 state: "An acequia or community ditch may establish a water bank for the purpose of temporarily reallocating water without change of purpose of use or point of diversion to augment the water supplies available for the places of use served by the acequia or community ditch. The acequia or community ditch water bank may make temporary transfers of place of use without formal proceedings before the state engineer, and water rights placed in the acequia or community ditch water bank shall not be subject to loss for non-use during the period the rights are placed in the water bank. An acequia or community ditch water bank established pursuant to this section is not subject to recognition or approval by the interstate stream commission or the state engineer." This legislation is aimed strictly at protecting community water rights from forfeiture due to non-use and differs drastically from former proposals which sought, primarily, to allow an acequia to lease excess water to users outside of the community system. Under the provisions of this legislation all banked water would be reallocated only to parciantes and land currently within the community system and would revert back to the original owner's land when that owner is once again able to put the right(s) to beneficial use. La Jicarita News will track both of these important pieces of legislation progress through the state legislature and give a full report of their outcomes in the April issue. Book Review: This Sovereign Land: A New Vision for Governing the WestBy Daniel KemmisReviewed by Kay MatthewsThis Sovereign Land by Daniel Kemmis, director of the Center for the Rocky Mountain West at the University of Montana and former mayor of Missoula, is a validation of everything those of us involved in community forestry and watershed restoration have been saying for years: The Forest Service has failed in its mission of forest stewardship and is incapable of meaningful collaboration with communities that are ready to get the job done. Kemmis puts it this way: "Watershed councils and other mechanisms of western collaboration have become both increasingly effective and increasingly incompatible with the prevailing centralized and adversarial decision-making structures on the one hand and with the region's arbitrarily bounded political jurisdictions on the other. The West may soon be prepared to recognize how consistently those old structures prevent the region from determining its own fate on its own terms. That recognition may in term enable the West to begin inventing institutions appropriate to a democratic people inhabiting a unique landscape." Kemmis believes that institutions like the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) have lost their governing legitimacy and it's time for western stakeholders to begin the real work of developing collaborative processes to govern our public lands. He develops his argument in the context of how national sovereignty and imperialism defined western settlement. He begins with the story of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife's attempt to introduce the grizzly bear into the Selway-Bitteroot region of Idaho and Montana during the 1980s, triggering a battle that so often leads to an impasse in governing the West. On one side stands the People for the West, funded by the extractive industry, that says unilaterally "No Bears!" (backed by the Republicans) and on the other side the national environmental movement that says "There are our national forests, they do not belong to the people who live here and you are not going to tell us how to manage them" (backed by the Democrats). Attempts by a coalition of people that represented both sides of this argument eventually failed, attacked by extremists who refused to relinquish their sovereignty to a group of local people who sought a compromise position. What this represents is the essential story of the West: the conflict between its development through the expansion of the American empire, or manifest destiny, and attempts at self governing, or local sovereignty. Kemmis goes back in history to follow the story of these two threads, empire and sovereignty, starting with an analysis of the presidencies of Thomas Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt, whose policies largely determined the shape and politics of the West. "Jefferson the imperialist" set in motion Lewis and Clark's expedition to find the headwaters of the Missouri and Columbia rivers that was largely an imperial policy expressed as manifest destiny, to gain the geopolitical control of the Pacific coast. "Jefferson the naturalist" made sure they took notes on the biological, topographical and hydrologic systems of the West. Kemmis goes on to trace this imperialist policy through the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase, the Civil War (largely fought over the question of slavery extending into western territories), and the Mexican-American War, to the time of Roosevelt, a hundred years later. Like Jefferson, Roosevelt was a naturalist, but he actually lived out his "western romanticism" by ranching and hunting throughout the West. It was here he recruited his Rough Riders, who followed him to fame on Cuba's San Juan Hill as he pursued his imperialist career in the Spanish-American War, the Panama Canal, and eventually the New Nationalism that "reserved" vast tracts of western land that were soon placed under the jurisdiction of the Forest Service. Kemmis points out that Roosevelt displayed a "deep ideological conflict" in his celebration of western individualism and heroism while at the same time pursuing an imperialistic agenda in nationalizing millions of acres of western land. It is this conflict that Kemmis believes the West has inherited from Roosevelt and that lies at the heart of its identity crisis: nationhood versus sovereignty. In his chapter "A Century of Rebellion" Kemmis explores the history of western resentment of national control that began with Roosevelt and his forest administrator, Gifford Pinchot. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 authorized the Secretary of the Interior to create grazing districts from unappropriated public domain lands. The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976 reaffirmed the ownership of BLM-administered lands in public ownership. This act elicited what came to be known as the Sagebrush Rebellion in the late 70s and 80s, when states tried to claim public lands as state property. Orin Hatch of Utah actually introduced a bill into the U.S. Senate that would have allowed states to transfer ownership of public lands to their jurisdiction. Environmentalists went to court to block the bill and the rebellion loststeam, until it resurfaced in the 1990s in Catron County, New Mexico. This time the county attempted to assert jurisdiction over all federal and state lands, waters, and wildlife in its Interim Land Use Policy Plan. This county movement, which initially spread across the West, also began to fade, but, according to Kemmis, led to "a less legalistic and more symbolic attack on federal land management in general" which is largely ineffective. But he goes on to say, " . . . the centralized system against which westerners have struggled for a full century has itself become more than a little pathetic as it grasps at ever newer formulas to maintain its governing legitimacy. Like two punch-drunk fighters, the Empire and the [Sagebrush] Rebellion both sag on the ropes, and spectators can only hope that the fight is called before they have to endure another round." What Kemmis sees in place of this fight is the relationship between a growing "global ecology and global economy" that decreases the authority of the nation-state and opens the door to regional and local forms of governance. He quotes an Oxford University fellow: "The . . . fragmented system of sovereign states [is] less and less able to guarantee the effective and equitable management of an interdependent world in general, and of the global environment in particular . . . . The [nation] is too big to develop effective strategies of sustainable development, and too small to effectively manage global problems such as climate change or biodiversity protection." This is the context, then, in which the Forest Service, described in a 1989 memo by forest supervisors as "an agency out of control", has become increasingly incapable of managing our public lands. The agency is demoralized from within, assaulted by environmental and property rights advocates from without, and, as described by its own chief, suffers from "analysis paralysis." The agency has also been manipulated from both sides of the political spectrum, by those who demanded it "get out the cut" after World War II at unsustainable levels and by the environmental movement that burdened the agency with endless paperwork and litigation. This has made it impossible for local managers to keep the promises they make to local communities. In the last few chapters of the book, Kemmis guides the reader through possible solutions to this gridlock. He believes it's time for the West to seize the moment and create a new regionalism where public lands are managed watershed by watershed or along geographic lines that define communities. He references John Wesley Powell, who, after his western explorations in the 1870s, argued that the West could not be effectively managed under national policies like the Homestead Act, which failed to acknowledge its unique geography and aridity. The only way for the West to devolve nationally is through the collaboration of people and groups who care about the places they live, who are intimately familiar with the ecology, and are willing to devote the time and energy it takes to solve issues such as species reintroduction, timber and rangeland management, and habitat protection. The process has already begun, and Kemmis highlights the work of such groups as the Malpai Borderlands Project in southwestern New Mexico, the Applegate Partnership in southern Oregon, the Ponderosa Pine Forest Partnership in southwestern Colorado, the Grand Canyon Forests Partnership in northern Arizona, and the Quincy Library Group in northern California. Most of these groups, however, have come up against the ethos of the Forest Service as "expert" that only wants collaborative help up to the point where decisions are made.This, Kemmis points out, "is fatal to genuine collaboration." How then do we make collaboration a force in western land management? Kemmis believes it is time to "begin thinking about realigning sovereignty to give westerners more control over public lands, not in order to exploit them or ruin them but for the long-term sustainability of western ecosystems and communities." One example he presents is the Three Sovereigns proposal in the Columbia River basin, where a compact among the stakeholders - state, tribe, and federal government - provides all three contracting sovereigns with the authority to manage the basin. Kemmis recognizes the importance of tribal sovereignty in the West but in a glaring omission neglects to discuss Hispano land grants. In their fight for restitution of their common lands now under federal jurisdiction, land grant activists have consistently called for the right to manage these lands to benefit the resource and forest-dependent communities. In the last chapter, "Realigning Western Politics," Kemmis challenges Republicans to get out of bed with the extractive industry, and the Democrats out of bed with the environmentalists: "If both western parties could more or less simultaneously let go of what no longer serves them or the West, they might also each carry forward half of a new, broad-based and therefore potentially potent western agenda." In the face of global economic, ecological, and social challenges it is more important than ever to "recall the nation to its deepest democratic roots." |

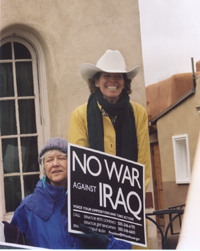

March Against War

Chellis Glendinning

Emma Simmons

Aspen Meleski, Aiya Ortiz, Mary Steigerwald

While the cause is serious, the mood at the march was festive. Thousands of people gathered at the Capitol Rotunda in Santa Fe on February 15, listened to speakers, shouted and sang, and marched to the Plaza to express their opposition to the Bush administration's march to war in Iraq. They carried signs that expressed their outrage - and their creativity: Regime Change Starts At Home; How Many Iraqis Per Gallon?; Amy Goodman For President; A Village In Texas Lost An Idiot; No Flag Is Large Enough To Cover The Shame Of Killing Innocent People (Howard Zinn); Stop Mad Cowboy Disease. Many New Mexico leaders and activists were there to show their support. Chellis Glendinning, Chimayó ecopsychologist, got the crowd laughing with her analysis of Bush and his administration in all their psychological and political dysfunction. State Representative Max Coll and Santa Fe County Commissioner Paul Duran were in the crowd. Land grant activist Roberto Mondragón and U.S. Representative Tom Udall marched to the Plaza. We all need to thank Tom for his courageous support of peace, voting against the resolution to go to war and the Patriot Act, an abrogation of our civil rights. He has been outspoken and responsive to his constituents, who have expressed their opposition to a preemptive strike against Iraq over and over again at town meetings in El Norte. Owen Lopez and his wife marched. Lynn Montgomery and Carol Miller held the Green Party banner at the Plaza. People came from all over New Mexico: Las Cruces; Las Vegas; Taos; Guadalupita (Rebecca Dayton); Albuquerque. Our own region of El Norte was well represented: the Badash family from Llano de la Llegua; Preacher Yunker from Vallecito; the Buechleys from El Valle; and Aspen Meleski and Mary Steigerwald, who live on an inholding high up in Las Trampas Canyon, left their hideaway to protest. Santa Fe artists Terri Rolland and Michelle Goodman demonstrated against war, as they do at all the marches and Friday afternoon protests on the corner of Cerrillos and St. Francis. Emma Simmons carried the sign Jews For Peace. As reports came in from around the world we knew we were in good company. Millions of people in London, Rome, Madrid, Paris, Manila, Baghdad, Berlin, Canberra, New York City, Los Angeles, and hundreds of other cities were also in the streets. And what is Bush's response? He dismisses us as a "focus group" that will not influence his resolve to protect American security. Exactly what "focus group" he's referring to is unclear, other than the common rallying cry against war. We are Catholics, Muslims, Quakers, Jews; we are Republicans, Greens, Democrats, Anarchists, Socialists; we are Americans, Europeans, Australians, Mexicanos; we are African-American, Hispano, Latino, Arab, Anglo; we are longtime anti-war activists, we are Veterans for Peace, we are first-time protesters, we are ordinary citizens expressing our anguish over the suffering and death that will result from this immoral war. &emdash;The Editors Keynote Speaker at the New Mexico Farming & Gardening Expo Talks RevolutionBy Kay MatthewsWes Jackson, keynote speaker at the New Mexico Organic Farming & Gardening Expo, gave a speech described by one participant as "brilliant but chilling." Jackson, co-founder of The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas and author of many books, is an erudite and impassioned advocate for revolutionary change in agricultural practices. At the Land Institute research farm he is working to help farmers switch from a monoculture annual grain cropping system to a more sustainable system of perennial polyculture grains. In his speech he explained that the monoculture systems that depend on annual plowing and the heavy use of chemical fertilizers create an environment of soil depletion and erosion, surface and ground water pollution and depletion, diseased animals, and exploitation of labor and migrant workers. Forty per cent of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded. Using the Mississippi River Valley as an example, Jackson described how the once rich, fertile soils created by glacial action and watered by Gulf moisture is now a "dead zone" because of the use of nitrogen fertilizers that have leached into the water systems. According to Jackson, as a result of the industrial revolution and our reliance on the technology that is inextricably linked to the capitalistic system, we have become an "agribleme", or agricultural blemish rather than a sustainable system that functions on "thrift, efficiency, discipline, and restraint." There is an imbalance in the social-political path that needs to develop alongside a technological-science economy that is speeding down an uncontrolled path: "We are headed on a crash course trying to feed the increasing population of the world unless we concentrate on sustainable agriculture that doesn't degrade the land. We have to learn to live with the sunlight coming in rather than the fossil fuels we currently depend on." Jackson's plan is to recreate the way the earth previously covered 90 per cent of itself with diverse perennials, whose roots prevent erosion and nitrate discharge: "Let's bring the diversity of the wildlands back to the farm." At the Land Institute, researchers are creating more perennialized warm season grasses, cool season grasses, legumes, and sunflower plants to create this natural system. The plants are then harvested with a combine cutter that leaves the seeds. So far, wheat, sorghum, rye, and sunflowers have been perennialized, and researchers are looking at perennialized corn and soy beans. He urged the audience to become more politically active: "The organic movement is not the end all and be all solution. We are taking the posture of the 'traditional looser', the ecological equivalent of an Uncle Tom. We are not proactive and we haven't deepened the discussion enough." He cautioned that commodification of the food supply makes food a weapon. For example, the subsidization of sugar in this country was used as an economic weapon against sugar-producing Cuba to retaliate against the Castro regime. We must instead use food to build community and to create a traditional society where we decide what technologies we want to take with us - like certain medicines that enhance the quality of life - rather than let technology continue to create power that is out of balance and out of control. "We need to rethink what we mean by sustainable and we need to be courageous about establishing a new economic system."  There were many other activities at the Expo, highlighting the theme of agricultural sustainability: understanding the new organic standards; soil fertility; the development of new Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) ventures; and many hands-on projects. Chris and Robin Hoult of Prairie Sun Farm came all the way from the Chino Valley in Arizona to talk about their organic farm operation that specializes in concord table grapes but also sells a variety of other fruits and vegetables. Above, Lynda Prim, director of the Farm Connection, co-sponsor of the Expo along with the Organic Commodities Commission, was presented with a framed edition of the first issue of the Farm Connection Newsletter, in honor of its tenth-year anniversary. |

Home | Current Issue | Subscribe | About Us | Environmental Justice | Links | Archive | Index

Copyright 1996-2002 La Jicarita Box 6 El Valle Route, Chamisal, New Mexico 87521.